Shezad Dawood’s Leviathan

British artist Shezad Dawood (London, 1974) is known for his multimedia practice that deconstructs systems of image, language, site and narrative. Dawood’s Encroachments, recently on at New Art Exchange, investigated the politics of space of Pakistan’s largest cities – Lahore and Karachi – in order to take an oblique look at US-Pakistan relations. Visitors virtually explore what Dawood refers to as ‘encroachments’, or illegitimate structures built on state or private infrastructure. His forthcoming project, virtual reality project Leviathan Legacy 2, is part of his larger Leviathan project that originally debuted at the Venice Biennale in 2017. Leviathan imagined the world 20-50 years from the present day in a series of films that explore the fault line between migration and climate change.

FRONTRUNNER spoke with Shezad Dawood on the artistic process behind these projects.

Encroachments entailed immense research not only into the history of US-Pakistan geopolitics, but also visual, architectural, and design history of Lahore and Karachi. How did this project begin?

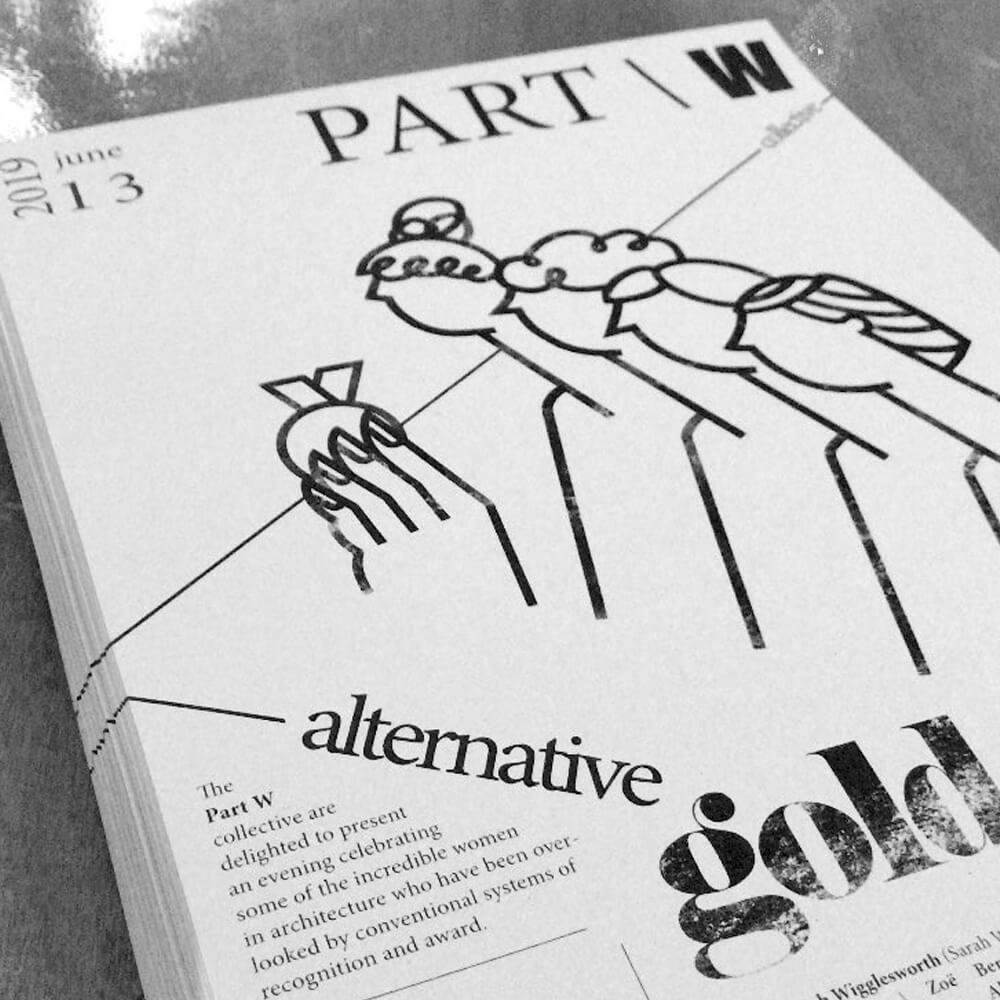

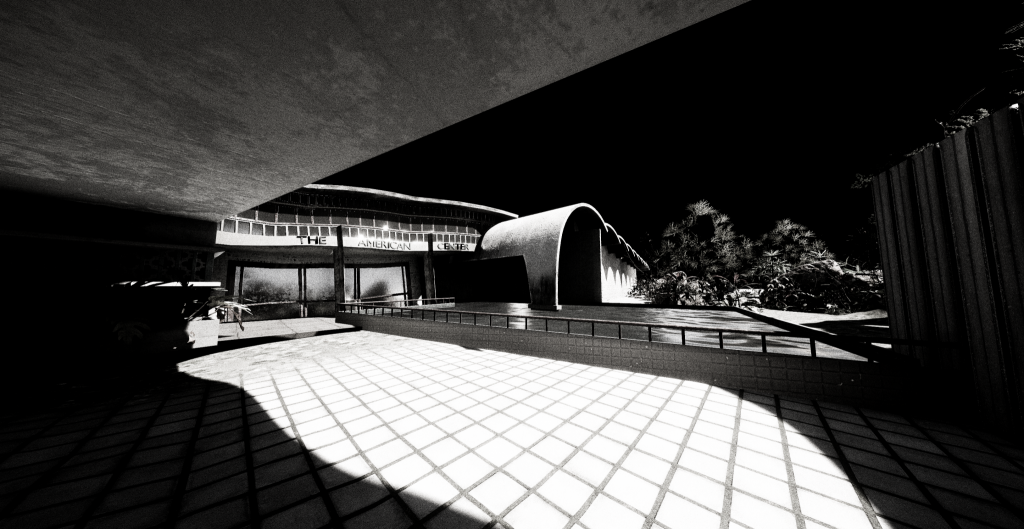

I’ve been working on an ongoing body of projects related to Modernist architecture in South Asia, and how Modernism in South Asia is so essentially connected to nation-building in the post-colonial period. Encroachments, the third of five intended projects, is centred on legendary California Modernist: Richard Neutra’s planned US Embassy in Karachi. Roughly half-way through the construction process of the embassy, Pakistan’s new capital city of Islamabad was completed, and so the final building was downgraded to a Consulate. For me, this is somewhat emblematic of the series of errors and misunderstandings that characterise US-Pakistan relations up to the present-day.

Encroachments (2019)

VR Environment

Co-commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation (SB-14) and New Art Exchange, Nottingham, UK

The background research is what drives the projects. There is a rumour that Neutra built on the site of a Sufi shrine (where an important Sufi saint was buried), who had cursed anyone who built over his grave. But it’s also about making visceral and emotional connections to sites. After years of negotiation – when I finally gained permission to access the site – perhaps the two most visceral elements for me were seeing the damage to the terrazzo floors, where the legs of the CIA’s super-computer (housed in the building during the Soviet invasion of neighbouring Afghanistan) had been ripped out by the State Department. On exiting, I couldn’t resist asking the elderly caretaker about the supposed Sufi shrine. He silently led me around a corner and pulled back a makeshift door, to reveal the shrine as if it had just been cleaned and maintained that morning. This confirmed the hypothesis, as remembered by Dion Neutra, Richard’s son in our email exchanges, that Neutra built around the shrine out of respect.

There are many moving parts in your works. Leviathan draws pivotal connections between marine science, mental health, and borders in order to investigate the fault lines between climate change and migration. How do you maintain a coherent narrative without losing complexity and nuance?

It can become a crazy juggling act, but I think that’s the key aspect of the work and the world- to be able to hold a set of interconnecting ideas in mind while finding a way to translate and communicate these to a wider audience. I couldn’t do that without a larger community of researchers, academics and specialists who inform the practice and have and continue to be very generous with their time and research areas. I look for unexpected connections and correspondences in these conversations with people working across various disciplines.

In the early research stages of Leviathan, I spoke with both Professor Cristina Cattaneo (who runs the Laboratory of Forensic Anthropology and Odontology at the University of Milan) and my friend Professor Susan Brundage (who directs Barts and The London School of Medicine, Queen Mary University of London, TRAUMA.ORG, and the Royal College of Surgeons England International Masters in Trauma Sciences Programme). They both made me painfully aware that I couldn’t talk about climate change and migration without factoring in the colossal mental health and trauma implications. This made me understand there was an entire layer to the problem I hadn’t fully considered.

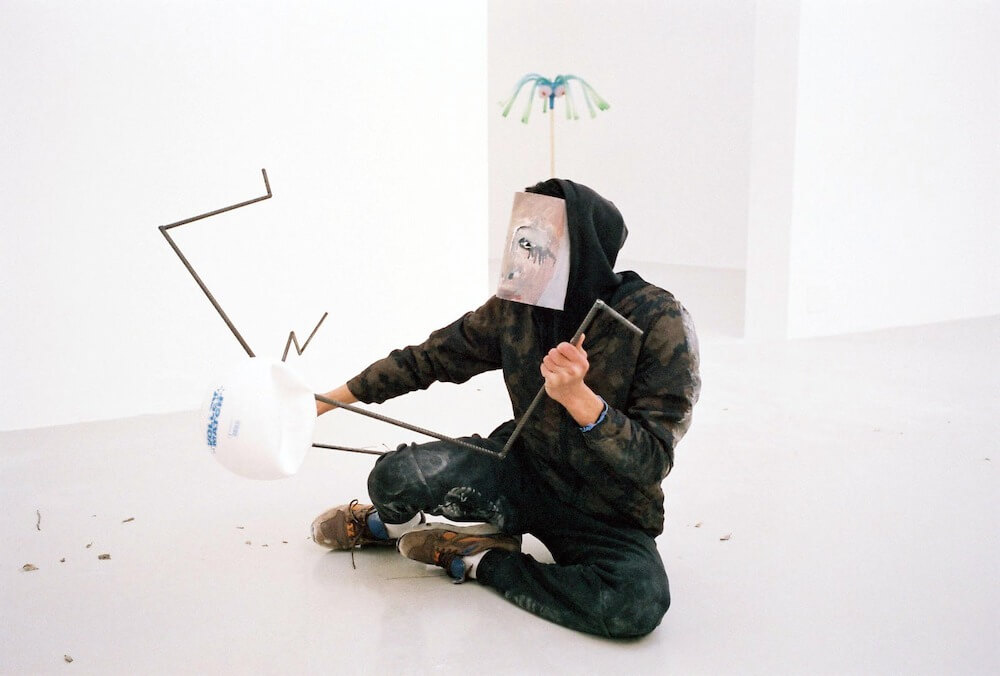

Leviathan Legacy, Part 1 (2018)

Production Still

Courtesy of the artist

It’s up to me to learn from these conversations and try to incorporate them within an evolving but coherent narrative, that people can get their heads around, without losing some of the subtleties of the argument. Sometimes I think this is possible within the visual realm, as being pre or proto-linguistic. It allows, say, via the editing process…a more visceral way to communicate. In Leviathan Episode 3: Arturo, I cut between shot footage of human gluttony and sexual excess (a nod to Pasolini) with documentary footage of overfishing, and the often overlooked cruelty of certain fishing practices, to draw a fundamental comparison between human appetites and the callousness by which we treat both our own and other species.

You work with film, sculpture, and painting in your installations. Can you speak a bit about your experience as a multi-media artist, from idea to medium?

The media I work with keeps evolving, particularly the digital which has an increasingly important position within my practice. It is very much a sense of sitting with and sketching ideas, and allowing them to find their final form. The ideas start to dictate their outcomes- whether something requires a specific angle of approach from the viewer or a specific idea of duration or acoustic or spatial sensibility.

Encroachments evolved from years of casual – what I call ‘background’ research – to a series of sketches and experimental paintings with embroidery, using denim from factories in Lahore. These, in turn, helped me to start to plan an installation combining the terrazzo floor patterns of my childhood in Pakistan, as well as starting to virtually map a set of key buildings to the project. The project didn’t really solidify until I was able to get back inside the former Consulate building with a film crew as an adult. This allowed me to import film footage back into VR – an unanticipated hybridisation of the analogue and the virtual.

Neon recurs throughout your installations, which aim to deconstruct image, language, site and narrative. How does the medium of neon help you to achieve this?

Neon also really comes from my childhood, where in the evening haze in Karachi a cornucopia of neon would seemingly pulsate and radiate signs, both sacred and profane, into the night sky. From Sufi shrines to the kebab shops generating the haze, each would beckon for your attention and attempt to sway you in its direction. This functioning of ‘light’ on the border of the metaphysical and the mundane, is what first attracted me to neon, an ability to be neither one thing nor another, but both simultaneously.

Island Pattern (2017)

Neon

129.5 x 200 cm

Installation view from Shezad Dawood: Leviathan at The Atlantic Project and Plymouth Arts Centre, Plymouth, UK

Photo credit: Andy Ford/Dom Moore

The 2020 Folkestone Triennial will feature Leviathan Legacy 2. How will this project evolve from the original series? What are the new central themes and ideas?

The Leviathan Legacy Trilogy, of which Leviathan Legacy 2 is the second part, was really an unexpected spin-off, of the main Leviathan ‘franchise’. Before Venice, a curator friend Ben Borthwick asked whether I’d be interested to develop a VR extension of the Leviathan project. Initially my response was a very definitive NO, as I was already due to create a 10-part film cycle. Though with a little breathing space after Venice, I’d found the hook which would make the VR different enough to the original films.

If the original Leviathan film cycle is set in an ambiguous 20-50 years from now, and interrogates where we might be and what the world might look like by then, the VR trilogy would begin on a beach in Cuba in 150 years’ time. For Leviathan Legacy Pt. 1, I worked with various marine biologists and engineers to imagine what the reef ecosystem might look like in the Gulf of Mexico at that time: from species, to symbiosis, to the background geopolitics. The whole Leviathan Legacy Trilogy becomes an exercise in where speculative science meets speculative fiction. Leviathan Legacy 2 jumps 300 years into the future, where sea levels have risen and the Kent coastline presents an open vista all the way to the Baltic coastline, and new hybrid species are to be found in these waters, but have they developed ‘naturally’ or have they been bio-engineered?

At this stage I will say no more, but that’s quite a good hint at what might be expected…