Rosie Elliott on Choreographing For Queer the Ballet’s “Dream of a Common Language” and Cultivating a More Inclusive Dance Culture

I first met Rosie Elliott during my first semester at Columbia University when I was cast in a new work they were choreographing for Columbia Ballet Collaborative– later titled “Plasticity/Hope”– and was immediately struck by how intentional they were in creating an inclusive dance space that prioritized the voices, needs, and safety of the dancers during the choreographic process. They began the first rehearsal with a partnering exercise that I had never encountered as a pre-professional ballet student, one that was designed to build trust among the dancers and open communication around consensual physical contact. Having decided to leave my intense training program to go to college and start anew, this felt like a refreshing introduction to the empathetic and community-oriented environment that would ultimately define my college dance experience. It’s also just one of many ways in which Rosie seeks to nurture a future for dance that better supports individuals’ well-being, agency, and self-expression.

In 2022, Rosie founded REmove Collective which aims to “remove the gender binary from ballet” and create more inclusive educational spaces in dance for individuals of all gender identities. Many dance schools use a split-up training approach with separate classes for male- and female-identifying dancers. Many schools also have strict dress codes that potentially limit dancers’ freedom in gender expression since they are expected to adhere to the code of whichever class they’re in (e.g. wearing a leotard and skirt versus a t-shirt and tights). The gender binary in dance is arguably built into and reinforced through many of its education programs since the training received in each of those two available classes is often quite different from the other. While there is significant overlap, the trainings often emphasize different skill sets. Possibly one of the most obvious examples is that female ballet dancers are expected to learn to dance on pointe, while historically, male dancers have rarely been given the opportunity to do so. Non-binary dancers are more or less made to choose one set of training or the other, or sometimes aren’t given a choice. In ballet partnering classes, individuals are also typically only taught one of two roles in partnering based on gender– to put it concisely, either “the supporter” or “the one being supported.” This additionally contributes to a largely heteronormative view within ballet choreography of what a pas de deux (and partnering in general) can look like.

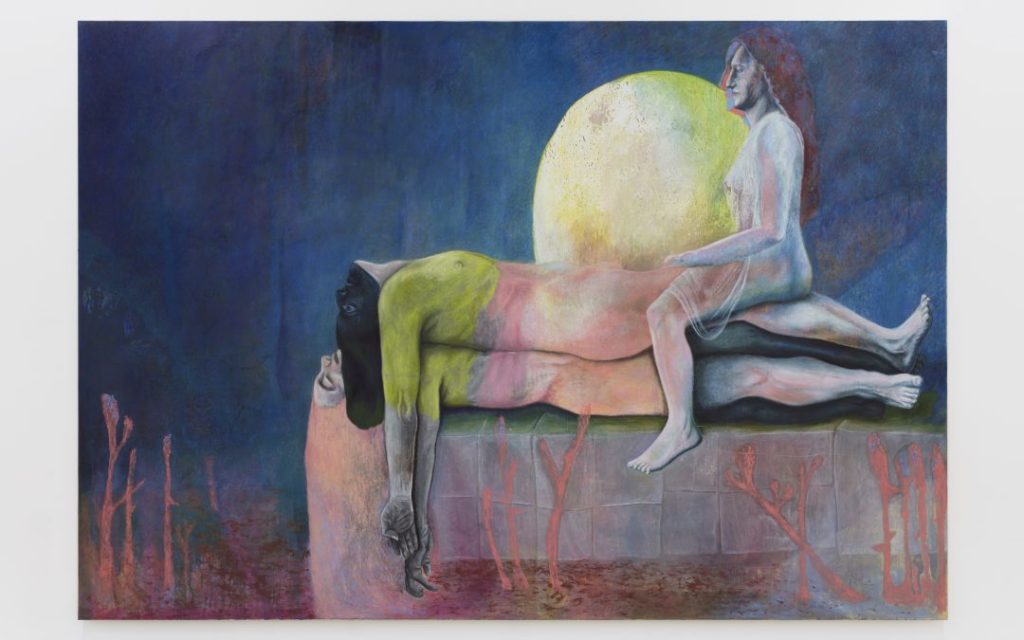

While researching pedagogical practices for gender-expansive dancers for REmove Collective, Rosie was looking for organizations that were doing similar work to what they were hoping to accomplish and came across Queer the Ballet (QTB) whose mission is to expand representation of queer experiences within classical ballet. Rosie met QTB’s founder and Artistic Director, Adriana Pierce, while on the leadership board for Columbia Ballet Collaborative after suggesting her as a choreographer for CBC’s Fall 2022 performances, and soon began working with QTB themself as the organization’s Director of Education. Most recently, Rosie choreographed alongside Adriana Pierce, Minnie Lane, and Lenai Alexis Wilkerson for Queer the Ballet’s new full-length ballet, “Dream of a Common Language,” which was performed at the Baruch Performing Arts Center from June 21st to 23rd.

In this interview, I talked with Rosie about their work on “Dream of a Common Language,” REmove Collective, and their efforts to improve the inclusivity of dance education. Responses have been edited in some places for clarity.

Queer the Ballet’s latest project “Dream of a Common Language” brings together the work of multiple choreographers to tell the stories of six queer individuals. How did the collaboration come about? Was it a sort of natural progression of the initial thematic concept to decide to involve multiple choreographers in one work or was it the other way around– did the concept evolve out of a desire to make a collaborative piece of choreography?

First, I want to just say how unique this structure is for a project but I think that to Adriana– because of the themes of the work– it was essential. This was not a split bill with multiple voices co-presenting their own work. Adriana and the project’s dramaturge Emily did the bulk of the work crafting the overall narrative guided by [Adrienne] Rich’s poetry collection. Adriana had a pretty clear artistic vision coming into the project but asked us which parts we felt we could best contribute to.

In my case, Adriana knew my work and suggested I tackle the “Dream of a Common Language” section. She had recently seen a piece I made for CoLab [at Columbia/Barnard] where the dancers were improvising on stage with a set score. It takes a kind of mind-melding to maintain cohesion and keep each other safe while also staying present in your own movement and improv tasks. I think she really liked the way I had directed that piece and saw that I would be a good fit to choreograph that DOCL section and execute her vision while also bringing in my own. For each of the choreographers, she had suggestions about the number of dancers, which poems to take inspiration from, and music selection, but was very open to our suggestions if we wanted to do something else. Emily was also available to us to discuss and analyze the poems or themes.

What was this collaborative process like, especially in relationship to one of the primary themes of building community and trying to find a “common language” among queer experiences?

In the actual rehearsal process, I often sat in on rehearsals for the other sections that I wasn’t choreographing. Maybe this is because I am the youngest choreographer (meaning I’m pretty early in my choreographic voice-finding process) but I was getting a lot of inspiration for my piece from watching Adriana [Pierce], Lenai [Alexis Wilkerson], and Minnie [Lane] build their sections. I was just absorbing it all – how they generate movement, how they direct the dancers, the way they go about queer partnering! I learned so much. I think my piece ended up having a lot of everyone’s voice in it. That was also kind of the point of my section. It was towards the end and it served to kind of pull different pieces of the show together before the big finale. In fact, towards the end of my piece, the three pas de deux’s that you’ve already seen in the earlier part of the show get up and repeat a section of their dances (which I didn’t choreograph) while the other dancers watch.

I think an important part of building a common language is also making space for difference. It’s not about glossing over the ways in which we all have very unique experiences and identities and ways of expressing ourselves. We wanted to maintain that and so I think we each also tried to show our unique voices but under one overarching narrative and shared goals about what we wanted to present and I think that really came through.

“Dream of a Common Language” was inspired by a poetry collection of the same name by Adrienne Rich. In what ways did you take influence from her work and how did this translate into movement composition?

My piece was more thematic than some of the pieces which were based on a specific poem. In my process, I read the entire collection multiple times and pulled out lines that resonated with me specifically as answers to the question: what is the dream of a common language? [Lines and phrases like,]

“We move openly together.”

We feel “the drive to connect.”

We “move effortlessly in our love.”

“I have never seen my own forces so taken up and shared and given back.”

I did a lot of free writing on this. I was reflecting on the question, ‘What does it feel like when we are seen and heard?’ I really did want it to feel like a dream where our most radical hopes and desires had been realized.

The beginning opens with each dancer entering the stage in their own style (one solo has small jumps, one does a series of bourrée’s and chainé turns). I wanted it to seem like they were discovering the space and their own bodies first, unaware of the others. As they start to see each other, they pause and walk around the stage, getting closer to one another. For the overall structure, I wanted it to slowly meld from these solos to a collective consciousness. There is a part where they all “try on” each other’s movement. They do a few steps from their own opening solo and then a few steps from someone else’s. I called that section “mosaic.”

We initially met because I had the pleasure of dancing in your piece for Columbia Ballet Collaborative in the fall of 2021, “Plasticity/Hope,” which is largely about the capacity of humans to adapt the way they think and consciously work on teaching themselves out of learned implicit biases (“plasticity” being a reference to the flexibility of the brain to develop, reinforce, and/or diminish different synaptic connections in neural pathways). The piece also explores the potential role of community in confronting those biases. Given your work on both “Plasticity” and “Dream of a Common Language,” what do you think is the role of community-building in social progress and understanding? Did your work on “Plasticity” influence the way you approached “Dream of a Common Language”?

The two works definitely influenced each other. In fact, there is a little section from “Plasticity” that I quoted in “Dream of a Common Language.” I think both pieces reflect a large sense of optimism I have about change and growth but yeah, I don’t think we can do it alone. Communities hold so much collective power. Adriana, through Queer the Ballet, is building such a strong community of dancers who are actively seeking change. It’s a ripple effect.

In working on “Plasticity/Hope,” we began the whole rehearsal process with an exercise that was all about establishing boundaries of contact for partnering. We paired up and actively showed our partner what we were comfortable with by guiding their hands over areas of our body that were “green” (where we were comfortable with contact) and hovering over areas that were “red” (where we weren’t comfortable with contact). Prior to that, my experience had mainly been that in partnering classes we were just sort of thrown into it all and expected to be okay with lots of physical contact from a fairly young age without being explicitly taught how to effectively communicate boundaries to a partner. I’m curious whether this is an exercise that you came up with or was it something that you learned from somewhere and decided to bring into your own rehearsal process?

I learned this from Sarah Lozoff! She is an intimacy director who works with ballet companies including ABT. She worked with us at Barnard when we were doing a piece with Christopher Rudd. Totally all credit to her on that. I thought it was so smart because nowadays choreographers make what to me are performative statements about consent. They might say “you can tell me if you feel uncomfortable” but no one is going to do that. That exercise puts the agency into the dancers hands to hold each other accountable for each other’s safety and comfort and also creates a mutually understood short-hand for “no, i’m not comfortable with that.” You can just say “that’s red.”

I understand that in addition to recently choreographing for Queer the Ballet you’re also very involved in the organizational side of it. What is your current role in Queer the Ballet and what kinds of work do you do as Director of Education?

When I started with them, I wanted them to absorb REmove so that we could start an educational branch of QTB. That’s still the plan, although funds and time have not really allowed that to take off yet. At the moment, I wear a lot of hats. I don’t think we have a traditional organization’s structure. We are very collaborative. Adriana let me choreograph for this huge show but I also do the budgets and balance sheets. We all have other jobs and projects so when we work on QTB stuff, it’s sort of a jump-in-and-do-what-you-can thing.

I’d love for you to tell me a little about REmove Collective. How did you first create it? What kinds of work do you do to try to implement changes to ballet education?

I started it through the Athena Fellows Program at Barnard. I spent a lot of time collecting information from students and teachers about their experiences and needs. The most tangible output was creating streamlined best practice guides for teachers to implement in their classrooms. I wanted it to be accessible to [everyone, from] the everyday teacher from a small studio to a university professor.

Do you get the sense that ballet is a bit “behind” many other workplaces or cultural institutions in the country in terms of its inclusivity and respect? Or does it more so provide a case study or example that mirrors the rest of society?

I guess I would say it is behind, although I don’t know if we can really make those comparisons. There certainly is much more diverse representation in other arts like television and film than in ballet, but I can’t speak to what that actually translates to in terms of inclusion and respect.

What do you see as some of the greatest obstacles to change in a lot of the culture surrounding ballet?

After seeing so many people working so hard to champion a new way of working I think what will get in the way of change is if others don’t look to those working for change and actually listen to what they are doing. There are practical limitations too like money and time. A lot of the people who are willing to devote themselves to this kind of work are doing it for very little in return and it can be unsustainable. We have to get the right people in the right positions with power to make effective change. We need more dialogue and action in the right direction.

I think plenty of people also get incredibly jaded and burnt out from many of the difficult aspects of the culture surrounding ballet and its resistance to change. Some decide to walk away from it because they feel like it doesn’t love them back or like they can’t be the fullest version of themself and still find acceptance in the field. What motivates you to stay with ballet and strive toward better work and educational environments, especially when so much of the rigid thinking in ballet– about bodies, about sexuality, about gender– is so heavily enmeshed in “tradition” that many teachers and repertory directors subscribe to or fall back on because that’s how they were taught?

I think that the distinction to be made is between ballet and ballet culture, teaching, institutions. I am so in love with ballet: its steps, structure, the drive to improve, the discipline. Those aspects have always attracted me to it. I think it’s a form I feel a responsibility to protect from all of the outside influences that distort it. Of course, we can’t separate ballet from the context in which it was created or the “tradition,” but we can try to hold its essence and potential up to the light.

Responses