Roland Gebhardt: A Minimalist’s Take on Identity

Roland Gebhardt is a New York based artist and designer. Born in Paramaribo, Suriname, he studied at the Kuntsgewerbeschule in Zurich and received a Master of Fine Arts from the Art Academy of Hamburg. He came to the United States in 1965. In 1974, he moved into his Tribeca studio and has been working there ever since. Using a minimalist approach, he creates sculpture-based art exploring the concept of the “linear void.” He has recently extended his sculpture practice to include performance with a focus on dance.

I stopped by Roland’s studio one afternoon in late February to talk with him about his new 3-D drawing series. We also talked about his career-long interest in identity and how he has been able to explore this very complex issue while maintaining a minimalist practice

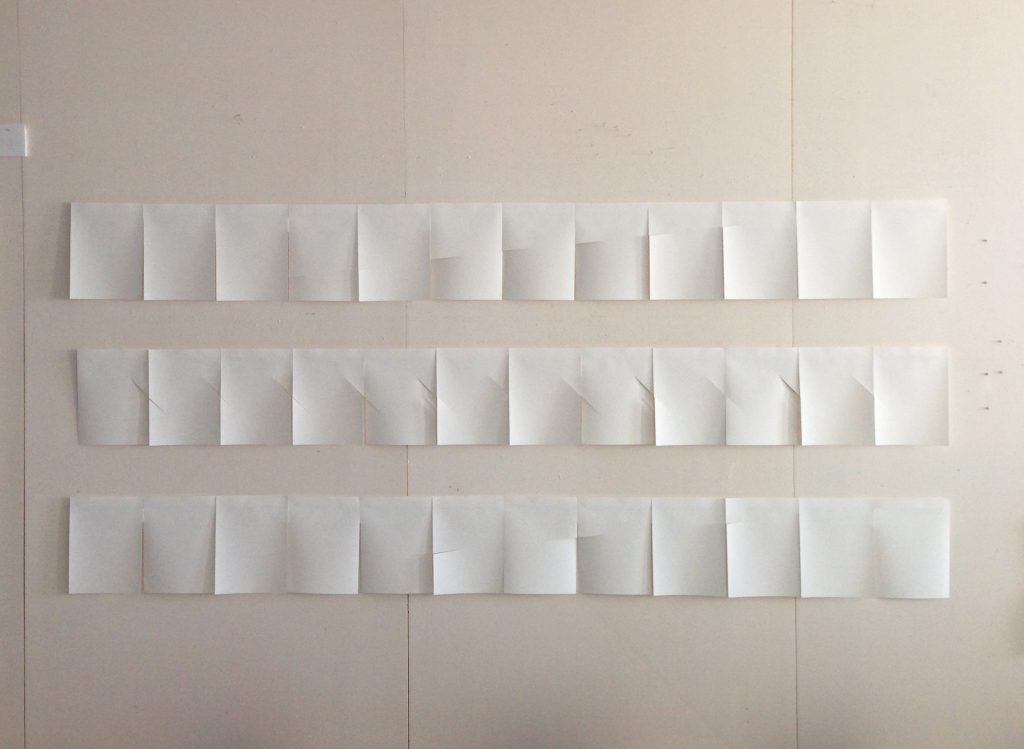

Your recent work focuses on the concept of 3-D drawing. How would you describe this work? What materials do you use? And what is your process?

It is sort of a name of convenience for a series of 2-dimensional sculptures made of paper, which are extensions of my earlier work with “linear voids.” I use paper because it is very convenient and quick to work with. Paper also has the quality of being ephemeral, and I have always been fascinated with ephemeral as a quality and concept in art.

I view a sheet of paper as a volume, and cut through it to establish a line, or void. This process results in a very large vocabulary that can be used for geometric iterations or explorations. It can also be used to connect a sheet of paper to lines on the wall. And because paper is so wonderfully expedient, I can do a lot of explorations in a relatively short period of time.

Also, when you hang a piece on the wall, it changes shape ever so subtly due to atmospheric fluctuations like humidity and light. It is like a living sculpture, and you would not expect this from something as dry and sober as paper.

Making incisions into objects was used in your earlier projects like Fresh Sculptures and Boulders. How did the choice of material affect the work process and outcome?

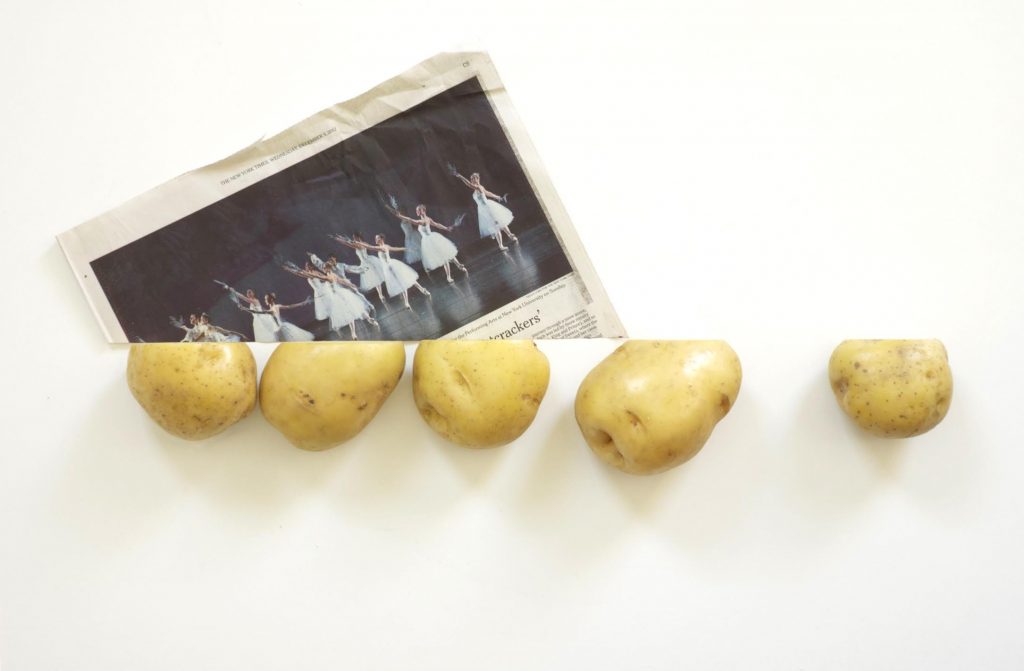

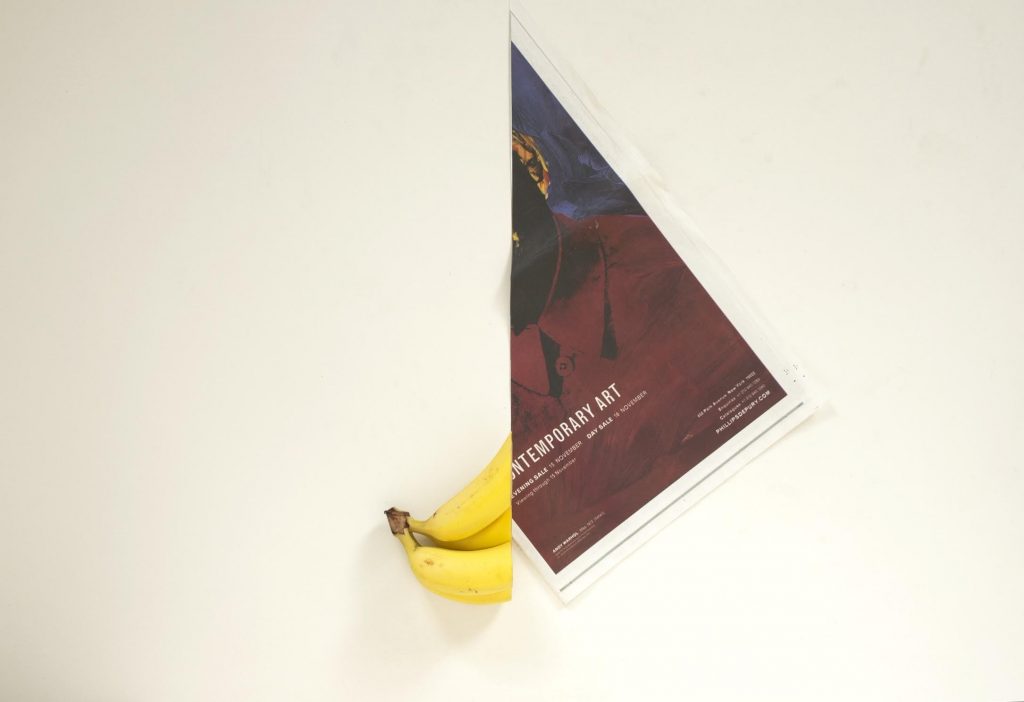

For an exhibition at the Kunsthalle, Duesseldorf, I placed linear voids into fruit and vegetables to connect them. Later, I explored this minimalist concept further by cutting a facet of various volumes and connecting them. For example, if you cut a facet of an apple and a facet of a book and connect them, a communication between the two objects is established. And your head can go with that wherever it wants to go regarding this communication. There might be historical and literal references, and I like to exploit that, sometimes in a playful and humorous manner.

For one work, I bisected a page from the New York Times with an image of wonderful ballet dancers. I then corresponded the dancers with potatoes that had been cut in half. So you have a visual contrast of the newsprint image with the starchy brown potatoes. Then there is a contextual contrast between the perfect and beautiful dancers and lumpy vegetables. This statement opens up a very complex language.

I also exercised this concept on other volumes such as stone, metal and wood. The expression of a line is very different in a block of wood than it is in a stone. So I juxtaposed them, and that juxtaposition contributes to the content of the work.

I was lucky enough to see Trophies performed at Jack Hanley Gallery in 2014. The project incorporates sculpture, dance, and music to explore issues of identity and transformation from living being to hunter’s trophy. What was your inspiration for the project? And how was your experience working with the dancers?

Pretty much all my material work has the theme of identity to it. Even a piece of paper has an identity, but the moment you cut into the paper, it changes.

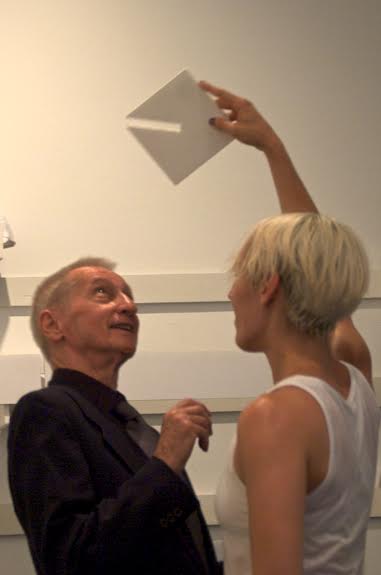

Being so interested in identity at a very abstract level, I could not resist doing masks, because masks are the ultimate mode of playing with and learning about identity. We start with peek-a-boo as kids, putting our hands in front of our face. Imagining about becoming somebody else, wondering how we can express ourselves differently – these are all things masks allow us to do. I was interested in seeing how masks would work with my minimalist vocabulary. Once they were on people who began walking around, I could not help but start telling stories. It became too complex to express these ideas with the mask alone, so I adopted performance.

In Trophies, there is the idea of expanded identity by focusing on rituals like collecting trophies. Here, we express our identity through the objects we collect and they become a surrogate for our personality.

The experience of working with the dancers was very new. One interesting discovery was the ephemeral nature of presenting the work to an audience through performance. The moment after a dancer makes a step, it is no longer there. Also, it is not my performance; it is the dancers’ performance. They interpret the masks and endow it with personality. It is another layer to the work where I do not have authority. Rather, I become an observer of my own expressions. There is a wonderful video in which Mercedes Searer, the choreographer for Trophies at Jack Hanley Gallery, takes one of the masks and plays with, preventing me, the collector, from taking possession.

Was that your role in Trophies? Were you the collector?

Yes, we did that because I was familiar with the masks and it was a shortcut. But I would love to do it with someone else in the role of the collector

The music was amazing. Can you tell me about the music you chose to accompany Trophies?

The music is by Moondog, a blind musician and poet who performed on 6th avenue between 52nd and 55th street from the 1940s to early 1970s. He would stand on the street selling his music dressed as a Viking with his helmet, cloak, and staff. He was well known as “the Viking of 6th Avenue,” an altered identity. His music is very mathematical and counterpoint. Because of these repeats, the melodies are very complex, ritual like I think. Moondog’s music really lends itself to Trophies, because it has this tribal sound with repetitions and beat.

In earlier works such as The Only Tribe and sculpture dance, you also used masks to explore the issue of identity. How did these works evolve? Where were they performed?

For The Only Tribe, I adapted a story by Rebecca Bannor-Addae about tribal behavior and order. The masks actually came first. Then when I discovered Rebecca’s story, I began working on The Only Tribe and realized it demanded specific masks to create different tribes. These masks were then used to create a sculpture dance series. In these performances, the masks were used in open spaces like Storm King Art Center and the Chautauqua Institution. The Only Tribe was performed at 3LD Art and Technology Center as part of a residency.

Even though your projects have varied drastically through out your career, your work has retained a conceptual minimalist aesthetic. Why do you think this approach to art making has been so agreeable for you?

I searched for and evolved a visual and contextual vocabulary that would allow me to say many things with the same words/expressions. I am dyslexic and as a kid, I could not tell different letter forms apart from each other. So maybe a minimalist mode of expression was something I needed to inform my art.

Also, I may have chosen a limited vocabulary for the opportunity to evolve and invite other aspects into it. Using books for example. Cutting into a book is a very minimalist act. But then there is the content of the book, and the image of the book, which will start communicating with an object such as another book, record, or apple, once they are positioned against each other. Contextually, they become changed objects. This vocabulary allows for a very rich conversation.

What do you have planned for Spring/Summer?

I am on a roll right now, so I will be doing more work with the 3-D drawings. I also hope to be cutting more stone this summer, revisiting earlier work with new insights. And I have a couple of planned projects that will take place in the Caribbean, but they have to do more with my design work.

Responses