Reveal and Conceal: A Conversation with Justin Fitzpatrick

I got off on the wrong foot with Justin Fitzpatrick. For some reason, my garbled mid-week brain mixed terms like Foxy Production, London, Los Angeles, Ireland and New York into one ball of confusion. Needless to say, I wasn’t too sure whether or not this interview would happen. Fortunately, here we are.

Justin Fitzpatrick is a London-based artist, born in Dublin in 1985, with an MA in Fine Art Painting from the Royal College of Art and graduated from St. Oswald’s School of Painting. In the space of a mere four years, Fitzpatrick’s work has been shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp, the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) London, the Barbican Arts Trust and commercial venues in Vienna, Paris, New York, Stockholm, Brussels, Dusseldorf and London. We spoke about his latest exhibitions, the origins of his illuminated works, and how they are activated in a constant cycle of reveal-and-conceal.

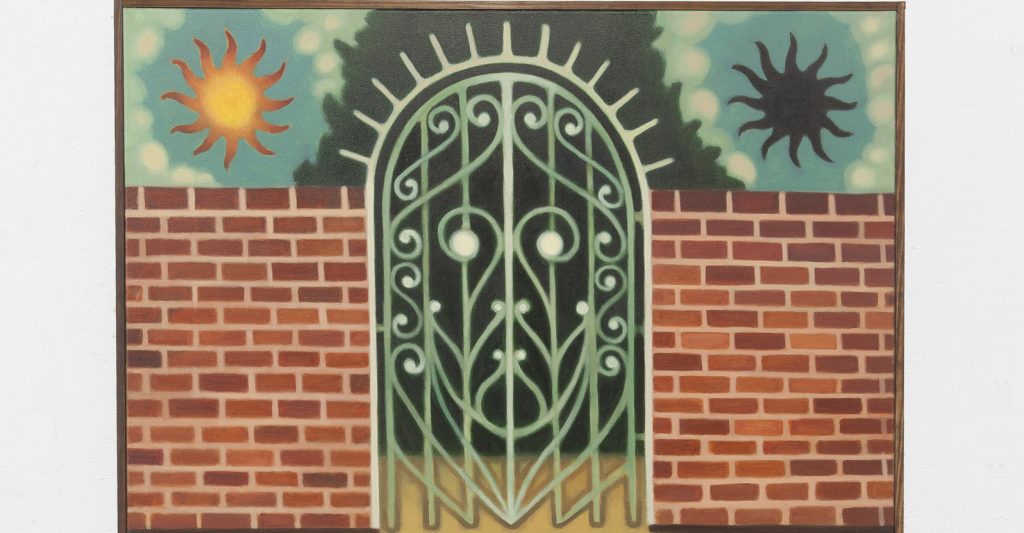

Paolo Uccello enters the annals of history (2019)

Oil on canvas, wooden frame

143 x 93 x 3.5 cm

Photo credit: Charles Benton

Courtesy of the artist and Foxy Production, New York

I’ve just read your text ‘French Garden’ that was produced for your F-R-O-N-T-I-S-P-I-E-C-E exhibition at Seventeen Gallery in London. Does creating prose in this way figure prominently alongside your practice as a visual artist?

I think it’s very important for me to be writing whilst making work, though it is rarely the case that this writing becomes a work in itself. Usually I use writing as a kind of machine to produce visuals for physical works. In this instance the text seemed to line up in an awkward but interesting way with that show. It wasn’t there to annotate the works themselves or explain them, but to run parallel. It was also a way to be explicit about my intentions in a way that the physical work couldn’t be. For this text I wanted to talk about the construction of ‘nature’ in relationship to the history of garden design, how that mirrored movements in French philosophy and of course more general claims to what is ‘natural’. I think I use text also sometimes as a kind of pressure release for the physical artworks I make, so they don’t have to do so much heavy lifting and can just be themselves.

There are potent reminders in your work that graphic illustration and medieval illumination still hold fascination for a general audience. How do you keep these tropes fresh in a world that is so saturated with “throwback” imagery and image consumption?

I don’t really have any great desire for keeping things fresh, to be honest! I guess I would like to have a painting practice that is quite flexible and accommodating, to the point that I could use different historical referents and their style would inform the reading of the work, so style becomes part of the vocabulary of the work and not something in it’s unconscious. I like the historic indeterminacy of it. Right now I am painting men dressed in lobster costumes, but I wanted to broaden it out from a direct cosplay/fetish position into a more mystic and romantic Pre-Raphaelite Edward Burne Jones feeling, or like a painting of a sphinx by Fernand Khnopff.

I definitely draw on medieval illumination, pulp sci fi book covers and advertising, also. The medieval illumination I am drawn to is the stuff I saw as a child in Dublin, the Book of Kells, where these hypnotising full page letter-forms would writhe with figures and animals and decoration. I find they are a really odd Christian art because they are so pagan in in their constant metamorphosis. They’re really libidinal and very internal, like an intestinal tract. They are a kind of hydraulic diagram, and they also express something really fundamental about image making, the mania of improvisation. I think my interest in graphic illustration and advertising is the idea of an image that has been weaponised in service of desire, images that are tasked with doing something, getting you to buy something. They’re affect but sharpened to a fine point, to the point of being manipulation. And if you make images that can’t help but be interesting.

Vehicle no 1: The White Glasses (2019)

Resin, epoxy clay, metal, pencil, paper

59 x 30 x 30 cm

Photo credit: Charles Benton

Courtesy of the artist and Foxy Production, New York

Tell me more about your background. You were born in Dublin (yes, rather embarrassingly I intimated that you were from L.A., don’t ask how) and completed your training at the RCA and St. Oswald’s School of Painting in London. What was life like before then?

I grew up in Ireland. When I was young I drew cartoons and made comics a bit. Our family used to do house-swap holidays to Italy and my parents took us to a lot of churches and museums. Surprisingly they were really into the idea of me doing art, though I think they wanted to nudge me towards that kind of capital-P painting. I didn’t really take the hint very well (I wanted to be an animator) but I did enjoy painting, though I think I enjoyed doing it more than I enjoyed looking at it. I think drawing cartoons really framed my perspective on painting actually, that it was for me focussing on visualising an interior world more than faithfully depicting the natural world. I am very into mannerism for this reason, as it concerns itself with an internal or digested view which imagines what things could be rather than what they are, not in a future-directed utopian logic but of a improvisational logic of mutation and of metamorphosis.

I sense you have an interest in inversions of circulatory systems: like revealing cutaways of the human figure, highway patterns, and botanical flourishes. How do you strike the balance between reveal and conceal in your work?

The two words you have chosen there are perfect; reveal and conceal, because that is exactly what is described in the work and it’s also a perfect description of the binary logic of the closet, of being closeted or being out. So for me this kind of obsession with in and out is a very literal way of looking at my own experience growing up, especially as someone who came out quite late. I had a whole internal world which was quite removed from my public self. Obviously everyone experiences this but when your sexuality is considered non-normative then you have maybe an exaggerated sense of it.

Having come out, you would think that this duality would all melt away and you could be your true authentic self but then there’s a realisation that there maybe was no essential identity hidden away but just a series of identity positions moving in relationship to the pressures applied on them from without and within. So even though I don’t necessarily want to subscribe to binary logic of in interior self versus external world, or what one withholds versus what one reveals, it is something that my work obsesses with, maybe as a kind of exorcism. Also I think by repeatedly pointing in the work to the thresholds of inside-outside (to skin, to doors, to apertures, to orifices) it kind of pokes holes (pun intended) at the idea of bodily integrity, personhood and individuality.

Paranoia and Parthenogenesis (2019)

Oil on canvas, wooden frame

143 x 113 x 3.5 cm

Photo credit: Charles Benton

Courtesy of the artist and Foxy Production, New York

You’ve had such a wide array of international exhibitions in the last six years in London, Antwerp, Vienna, Paris, New York and now Liste in Basel this summer. What would you say or suggest to a younger artist out there who might not have the reach or resources to cast such a wide net?

That’s a tough question. I think I have been very lucky and I’m really grateful for it. I think having resources ( I’ve interpreted it as financial resources) is a really important topic in the art world at the moment, and at all levels from individual artists to the questionable origins of institutional funding. At the individual level: there are two tiers of artists, the ones who have the independent means to survive and the ones who don’t. If you don’t then you have an endurance test of precarity to see how long you can last or how much you can borrow before your practice pays for itself or you have to bow out. When I started getting more invitations to do shows at some stage I stopped doing art technician and teaching work to have more time to make work. This led to about a year or so of the most precarious living I have ever experienced, where I had no idea when money would come in or indeed if it would and I had a bit of a nervous breakdown because of it. Thankfully it all paid off and things are going well now, but it was a very risky gamble on my part.

In terms of reach I think I had a sequence of opportunities, but the first one was from studying my Masters and then from that came New Contemporaries, and half a year after I was included in a show at David Roberts Art Foundation curated by Vincent Honoré, which was a huge opportunity and one I am really grateful for. Doing my masters was fundamental to getting that initial visibility. However, and not to be too one note about this, I’m not sure I could fully recommend my path to someone now, even though I had a great college experience. I started my masters just when the university fees went from around £3000 a year to £9000. Pragmatically my advice would be not to overextend yourself, like I did. I am disgusted by the political party that engineered the marketisation and privatisation of education and the unrepentant dismantling of social mobility through the false logic of austerity.

What is the best piece of advice you’ve ever received from an artist or creative person you admired? What was the most useless piece of “advice”?

I can’t recall any useless advice which is just as well but for the best piece of advice, I just read a quote recently so it’s fresh in my head: ‘ Work as if you live in the early days of a better nation’. Alasdair Gray, the Scottish author of ‘Lanark’ said it but he didn’t originate it. Right now it feels appropriate as it’s very easy to be mired down in the end-of days mood of now, but this quote feels like it points a way out of it, at least at an individual level.

A Pulsation of the Artery

Installation view, 2019

Photo credit: Charles Benton

Courtesy Foxy Production, New York