Readymade as Territory: Alexandre da Cunha

“My first affairs with art started very early in my life. I can see now that a lot of my daydreaming as a child relates a lot to what I do, professionally, as an adult”. Brazilian artist Alexandre da Cunha (b. Rio de Janeiro, 1969), based between London and São Paulo, created his signature with readymades. He never lost his origins and life experiences: to reinterpret objects and materials to then be reborn into an unprecedented form. Interpretation is often synonymous with intertwining cultures, travels and aspirations.

For his first solo exhibition in Italy, da Cunha’s Arena opened at Thomas Dane Gallery’s outpost in Napoli. Curated by Jenni Lomax (director of the Camden Art Centre in London from 1990 to 2017), Arena presents works that draw from Neapolitan culture. da Cunha found his energy while walking around the city. Marble (2020), for example, recalls the marble veil of the Veiled Christ by Giuseppe Sanmartino, a unique sculpture preserved in the Museo Cappella Sansevero. Coconut Figure III (2020) is made with a basin, light bulb, tap, coconut, wiring and fittings; it echoes the Aedicula (or small shrines) found in the alleys of Napoli made for religious devotion and to illuminate areas of the ancient city centre.

To understand his modus operandi and artistic strength, da Cunha’s Instagram account (the only social media he subscribes to) presents some works made from any found material – even food! da Cunha tells FRONTRUNNER about his life in art, his childhood, and his education.

When did your adventures in art begin?

My parents were very supportive and gave me a lot of incentive to develop my interest for arts, in general, alongside my formal education. We relocated as a family quite a lot, which played a big role in my artistic path and kept me curious and doubtful enough about the world and my surroundings. I believe that is somehow the core of any artistic path. In terms of art education, I started doing art courses as a teenager and made connections with a group of great artists in Belo Horizonte. They were huge influences, and those connections led me to a few shortcuts to my way into formal art education. I never fully adjusted to the formal structure of art education at university in Brazil. When I moved to London to do my MA about 20 years ago, the story changed and I started enjoying art college where I had a much more open dialogue with tutors, other students and the art community in general.

How are your readymades conceived?

Since I started making any work, I always felt inclined to use stuff I found around me instead of creating shapes out of any material. It started as a genuine concern for spending time looking at familiar things and materials, asking myself questions, and gradually forming a new vocabulary based on inferences from known structures and everyday objects. In time, I learned that this system presented endless possibilities in itself, and the apparent simple combination of objects was, in fact, a very complex process. It takes a really long time to be good at this type of work that seems effortless, almost invisible, or even a bit lazy at times. I don’t feel totally connected to the classic notion of the Duchampian idea of the readymade, as my approach to materials and found objects involves a great deal of rendering of the surfaces, polishing, and finishing up here and there. It’s all about control and order: it is, in fact, the opposite of a fortuitous encounter with one thing and its displacement. Usually I am interested in the cultural use of an object and not in their aesthetic, alone.

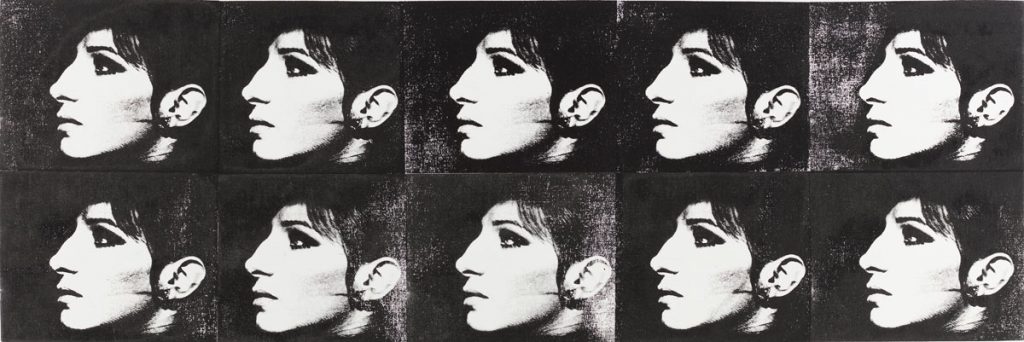

Arena

Installation view, Thomas Dane Gallery (Napoli, Italy) 29 September 2020 – 27 March 2021

©Alexandre da Cunha

Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery

Photo credit: Maurizio Esposito

One of the most common elements in your work is concrete. Why and what does it represents for you?

I grew up in Rio de Janeiro. Years later, I lived in São Paulo for a long time, which I now call my home city in Brazil. In both cities, concrete feels like a very natural part of the landscape and is present everywhere – from iconic landmarks to improvised structures on pavements where things are constantly changing. So, I developed this very natural connection with the material. It’s a type of bonding material and is surprisingly malleable. I’ve learned different ways to work with cement and concrete in the studio in a more intimate and intuitive process. More recently, I started working with precast concrete and using existing industrial structures to form large-scale works that usually go outdoors.

Mandala I (2014)

Linen, string and cleaning mop

200 x 200 x 4 cm

Private collection, London

Courtesy of the artist

Photo credit: Richard Ivey

Some of your works are giants. What’s the most difficult work you’ve done? Why?

It’s hard to name the most difficult work. Often, the most difficult works are ones that look very natural to make, but are actually very hard to resolve, formally. I might make something in the studio that I am very happy with, but I can spent the rest of my life trying find a good way to display it. I have works that are considered successful, but I feel that I haven’t fully resolved them yet. That used to bother me a lot; now I understand that this is a fluid and ongoing dilemma. The only way to engage with this process is to keep doing it and embrace the bumps on the way, pretty much like any other life practice, I suppose.

Obviously, large-scale and public commissions are challenging as they involve many layers of technical stuff, and working with a lot of people. Another aspect that’s very difficult with public commissions is the responsibility of the public. Most public sculptures are done with very little public consultation: they’re often perceived as a benevolent acts, gifts to communities. I started working with public sculptures a few years ago and felt very uncomfortable, initially. As if I was invading the public space with my ideas. I’m much better now at negotiating that tension with the public space and am finding surprising and very rewarding aspects, as well. But yes, public works remain the most challenging.

What feeling drives you to choose an object? Where do you find them?

It is, again, a long process. It usually starts by collecting found and industrialised objects. I’m often drawn to an object because of its form, but I get more excited about them when I see connections with the narratives behind them and their cultural history. I like to think of them as triggers for dialogues that go beyond their shapes. I find them walking around, travelling, being lost on my way to a place. I also find them online, on eBay, etc.

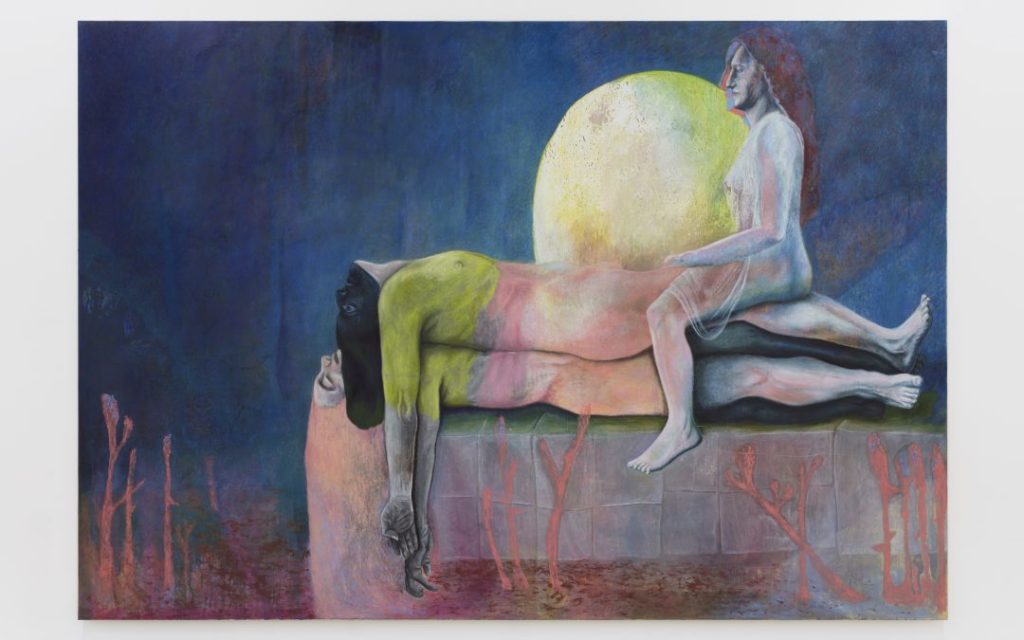

Arena

Installation view, Thomas Dane Gallery (Napoli, Italy) 29 September 2020 – 27 March 2021

©Alexandre da Cunha

Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery

Photo credit: Maurizio Esposito

How was your exhibition Arena conceived?

The concept of Arena as a solo show was developed in collaboration with Jenni Lomax. We made a few visits to Napoli together and had a decent amount of time to explore the space and its architecture. From the beginning, we knew that we wanted to form an exhibition that would establish a dialogue with the history of the buildings and the city. But the challenge for me was to do that, and allow the works to be seen independently at the same time. It was a privilege to work with Jenni, as we’d worked before. She was one of the first curators in London who paid attention to my practice and understands my work well. So, our dialogue is always very fluid all the time. Another really important aspect was that the gallery gave us total freedom to create a show without much pressure to present brand new works, which is a model usually employed by most of galleries. We revisited a few earlier works and displayed them with a body of new work, establishing different possibilities for the viewer to engage with my practice, in general.

Your work documents the territory, but also your own origins. In this case, what inspired you within the city of Napoli and what did it give you?

I’ve been using geographical and cultural references as part of my work for a while. Some titles come from product brands, their origins are not necessarily mine. Often, locations function as a sort of noise in the work; it give clues to the viewer to engage with a narrative, or sometimes adds a level of distraction. As we know, Napoli is a deeply inspiring city. It’s one of those places that everyone has fantasies about it. The city is often pictured in novels, films, documentaries and is essentially a very edgy and charming place. I fell in love with the city since my first visit, and go back every time I can. I feel at home there. It reminds of parts of Rio and São Paulo, and I love how mad and elegant it is, at the same time. It’s hard to say what inspired me because the whole experience of Napoli – or just simply walking around and getting lost – is always highly inspiring. For the work Kentucky (Napoli), made of dyed cleaning mops, I used colors that reference the tonalities of buildings in the city, but it was never meant to be a literal, formal reference.

How did you manage during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Unlike other people who might enjoy a certain level of isolation and quietness imposed by the pandemic, I struggled every single day. As I mentioned, my work is somehow a fruit of transit between places, cities, walks and conversations. So, mostly it’s been a huge challenge for me to keep working and believing that it makes sense to work in a broken world. But I managed to travel to Napoli and install quite a complex exhibition, and that was very important for me. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, I was forced to focus on the works, only, and not on other social interactions that usually come together with a big solo show like that. It was very quiet and introspective; all the work had to survive without much celebration or other distractions. It was a big test for me and for the work, but looking back now, I think it was possibly one of the most accomplished shows I have done.

I keep getting amazing feedback, perhaps because people had more time to see it, to make connections with previous works, with the space, with the light, etc. This is how artists work in general: taking all those aspects into consideration. But most of the time those subtleties are lost because people are rushing to see more, to go to another exhibition, to travel to another place. Apart from that show, I managed to work on other commissions that I could carry on without being in the studio and installed a large concrete sculpture in a show at The Box in Plymouth, U.K. That was also very technically complex. It’s a monumental work placed inside a historic building. A huge challenge.

Arena

Installation view, Thomas Dane Gallery (Napoli, Italy) 29 September 2020 – 27 March 2021

©Alexandre da Cunha

Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery

Photo credit: Maurizio Esposito

What are your upcoming projects?

I’m currently working toward a solo show at CCA Brighton, where I’m showing some pieces from the show in Napoli with other works. I’m enjoying this slower pace a lot, where I allow myself to install the same pieces twice and establish different conversations between works. It’s also a chance to let more people see the works that were presented in Napoli. I am now working on the final stages of a large, permanent commission that will be installed at one of the new Underground stations in London (Battersea Power Station). I’ve been developing this project for a few years, now. I created two very large panels (one is nearly 100 meters long) using a rotating advertising billboard mechanism that have no text or images. They are two huge friezes with gradient colors that will move slowly; the work is a reference to the idea of cycles, routine, repetition. As I mentioned earlier about public works, this will be a big challenge, but I’m very excited about the scale of the work and, of course, the possibility to place a permanent work at such an iconic site in London.