Jesse Chun: Home As A Metaphor

“My notion of home–or the way I like to challenge the existing notion of home–is that home is not necessarily a stable thing. It can be in flux and fluid,” reflects Brooklyn-based artist Jesse Chun. Applying her astute observation to her multifaceted body of work, Chun employs methods of appropriation to digitally and delicately alter, intervene and recontextualize the often impenetrable dominant institutions that define home as a static place, as well as a materialistic aspirational goal. Whether transforming imagery from passport watermarks into boundless landscapes in On Paper or abstracting segments of interior design magazines in her Other Interiors series, Chun’s art constructs new narratives that more faithfully reflect our increasingly mobile and globalized world.

Chun’s artistic interest in transience originates from an unquestionably personal source–her own experiences with migration and displacement. Born in South Korea, Chun has lived in numerous cities since her childhood including Seoul, Hong Kong, Toronto and New York. Taking inspiration from maneuvering through the intimidating bureaucratic red tape of immigration, as well as finding her own form of belonging wherever she resides, Chun allows viewers to question their own relationships to home.

Visiting her home-studio in Carroll Gardens, we spoke with Chun about the potential power in appropriation art, her definition of home and how she would like to affect viewers.

In your series On Paper, you appropriate government-issued documents such as passports to address ideas of identity, immigration and fluidity. How did you begin using these bureaucratic sources as artistic materials?

I started in grad school when I was working on my thesis. Prior to that, I was investigating the materiality of this traditional Korean paper called “hanji.” In Korean, the paper literally means “the paper of Korea.” I thought it was interesting that paper can really define a culture or symbolize something. I started thinking about my immigration documents because I’ve had to fill them out when we moved to Hong Kong from Korea when I was young, when I moved to Canada and when I moved back to New York. I started looking at my own archive of immigration documents. I just felt like instead of trying to recreate it, what’s more interesting is taking something that already exists, recontextualizing and adapting it. That’s when I started appropriating immigration documents and passports. I think a lot of my work is investigating imagery and text on paper.

At Fridman Gallery, New York, NY. Curated by Elisabeth Biondi.

Looking at both On Paper and Other Interiors, I keep thinking about appropriation as a form of the cut-up technique. As William S. Burroughs used to say, “Let’s cut it up and see what it really says.” What inspires you about appropriation?

I think what’s really freeing about appropriation is that I’m using something that other people can relate to. It’s not something that I’m making for myself only. It’s something that someone else might have used, been aware of and experienced. I like that universality. I feel appropriation–for me–is very freeing. As you were saying, I like the idea of dissecting and reducing down to the very essence. In some of my artist statements, I wrote how I’m employing the role of the artist as editor. I see myself as an editor and translator of things that exist that I try to decode. For me, appropriation allows me to do that, whereas if I made it from scratch, maybe it would lose that essence.

Home is a reoccurring theme in your art and you even work in a home-studio. How do you define home?

I definitely don’t think home is a physical place, a geographical place or location. I think it could be a mental space or an interspace. Sometimes I do think about how it’s not a place, architecture or country that makes me feel at home, but it’s the people–whether it’s family or friends. To me, it has a lot to do with relationships and the sense of belonging. I think that’s something I’d like to keep exploring and not just define.

You were born in South Korea and have lived in many different places since your childhood. How have your own experiences influenced your work?

I think it gave me a foundation and a context for my work because it’s my personal relationship and experience of globalization that have inspired my investigations. Had I not lived everywhere, maybe I wouldn’t deal with this sense of displacement and these questions of home. I think my personal story and background is definitely a starting point for my work.

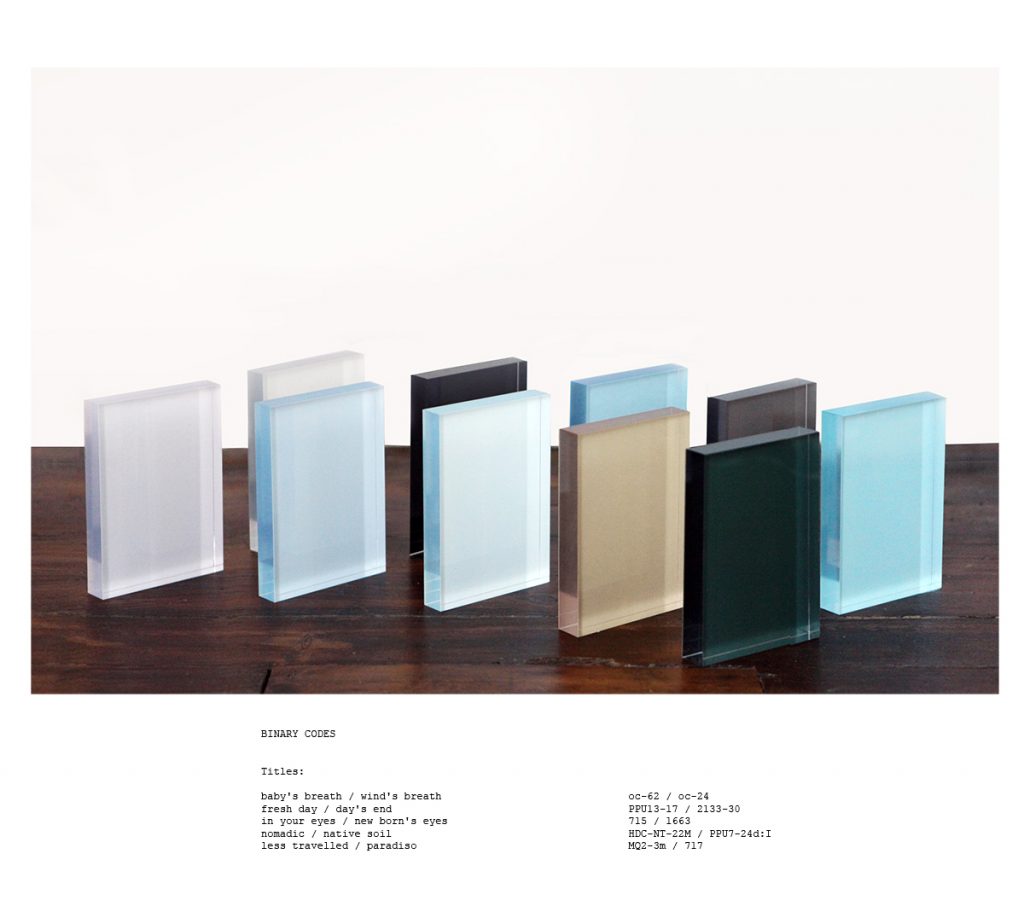

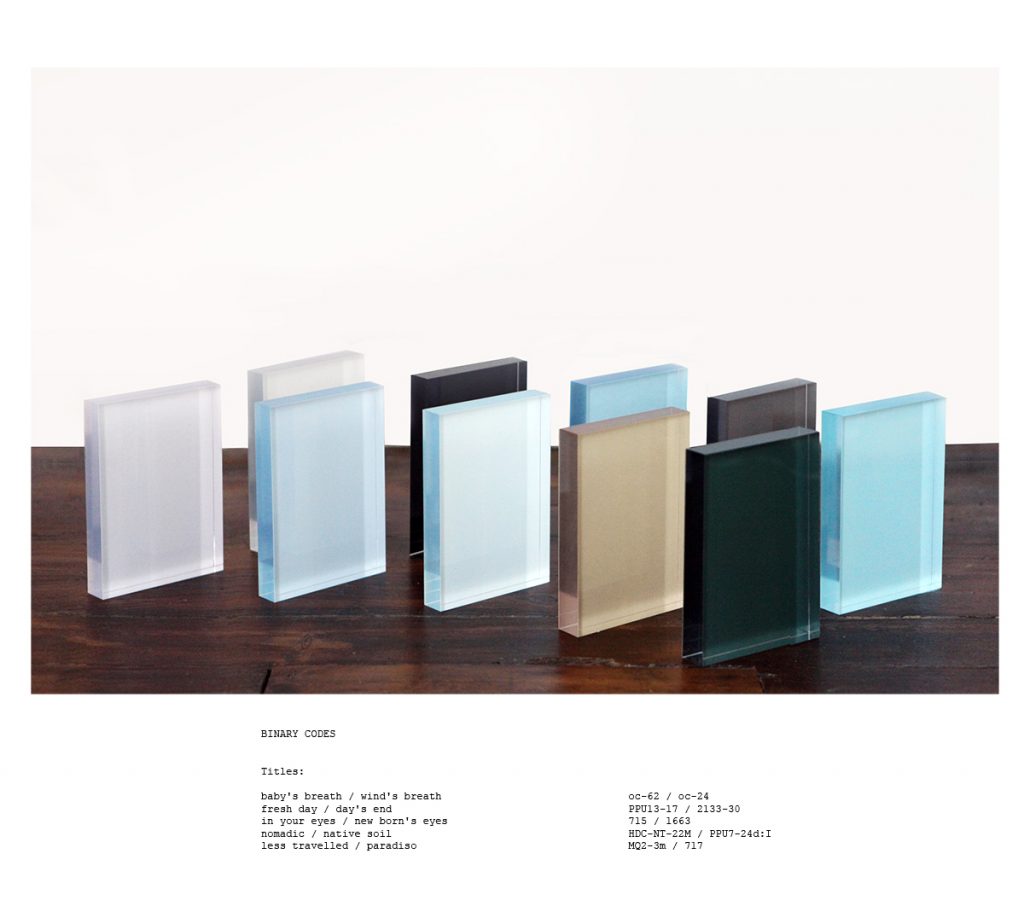

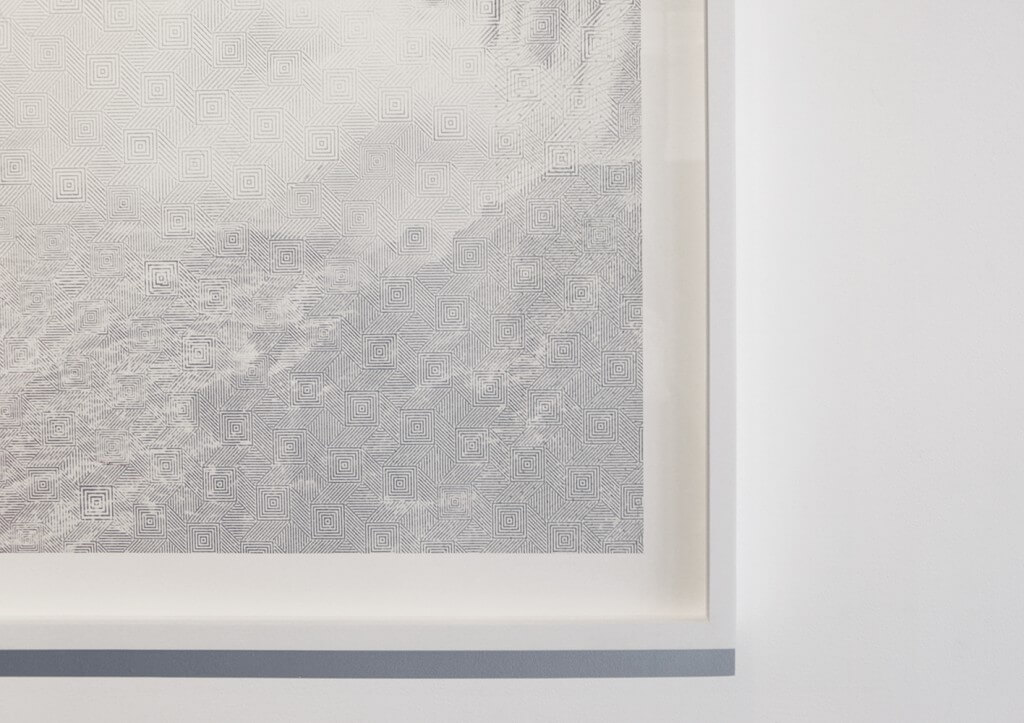

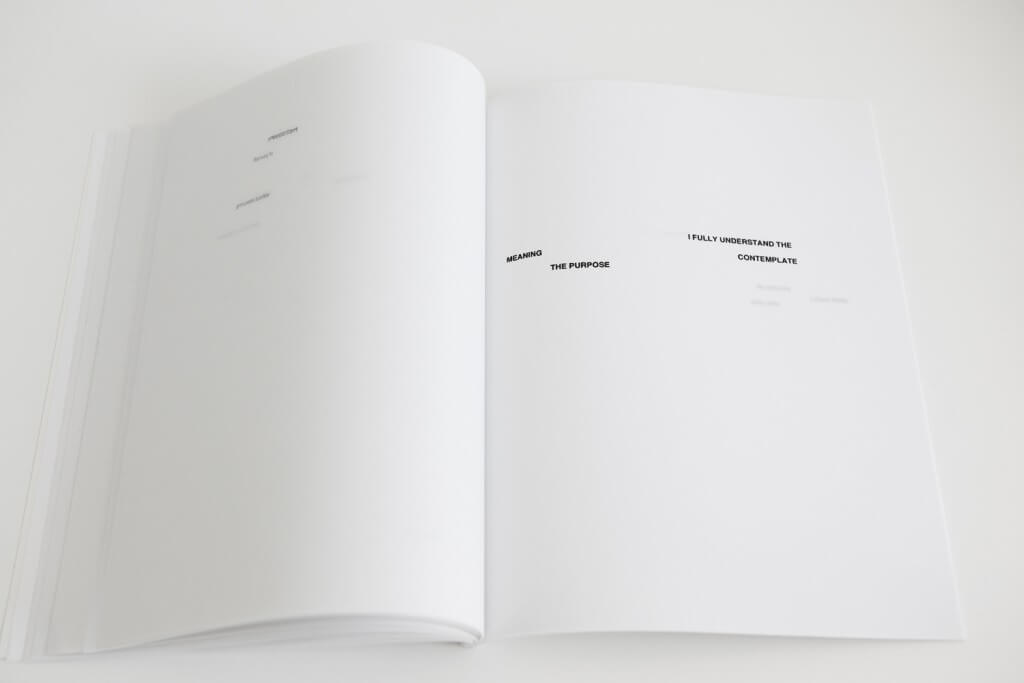

Your work also features a distinct literary aspect whether your sculpture titles based on paint swatch names in Other Interiors or your artist book Valid From Until, in which you selectively erase sections of your own immigration papers to form a poetic narrative about place. What interests you in the combination of poetry and visual art?

I grew up reading poetry. When I was six, I wanted to be a writer. Apparently, I wrote novels for my parents and that was my gift to them when I was five or six. They were like, “Ok…” I was always interested in literature and then, I found visual art. Basically, they’re both my passions. Poetry can speak to me in the same way a visual art piece can. For me, when I mix the two, it’s really interesting.

How would you like to affect the viewers of your work?

I think if I can get people to question what home really means instead of being comfortable in the frameworks we’re already set in–interior design magazines telling us we need this beautiful home or people feeling that home has to be this place that you grow up in where you have to know everyone. Not that everybody is telling you that, but there are these preexisting iconographies of home and aspirations of home. Because of how globalized and mobile everything is now and how people can be displaced, I think it’s really interesting to think about home as a metaphor rather than a place or a culture. What can that mean and what does it mean to belong? If I can get people to really question that, I think that’s enough for me.

Responses