Do What You Must: A Q&A With Ryan McCann

Ryan McCann has no other choice. “If anyone is consciously considering becoming an artist, I’d say, do anything else,” says McCann, with a combination of self-aware lightheartedness and actual frustration, “This is something I have to do.” McCann isn’t typical, even as atypical as artists go. Before taking up a full time art practice, the painter and photographer was a professional football player for the Cincinnati Bengals. While most actors wait tables to pay the bills, McCann acts to keep a studio. It is being an artist that he considers the most difficult job, yet. By-and-large self-taught, McCann’s is peripatetic in his styles, trying on distinct visual languages to suit the moment. With two new bodies of work in development McCann recently sat down with us to talk about the difficulties of infiltrating art world cliques, why Rene Magritte is an inspiration, and why he chooses not to focus on any one style.

You move between a variety of styles, from word art, to these very evocative and painterly photographic portraits. Honestly I wouldn’t suspect all of it was by the same artist. Why so many styles?

I use different styles to convey specific messages or emotions. Someone might have come across an image I made at some point and thought it was cool, but because there isn’t such a clear connection to other works, people often don’t make the connection back to me. This can be very difficult, but it’s the most honest way I can approach my life and my work. These styles come from a place of pure excitement! I even have to put the reins on myself because I get excited about a lot of things. I try to listen to the voices that are the loudest.

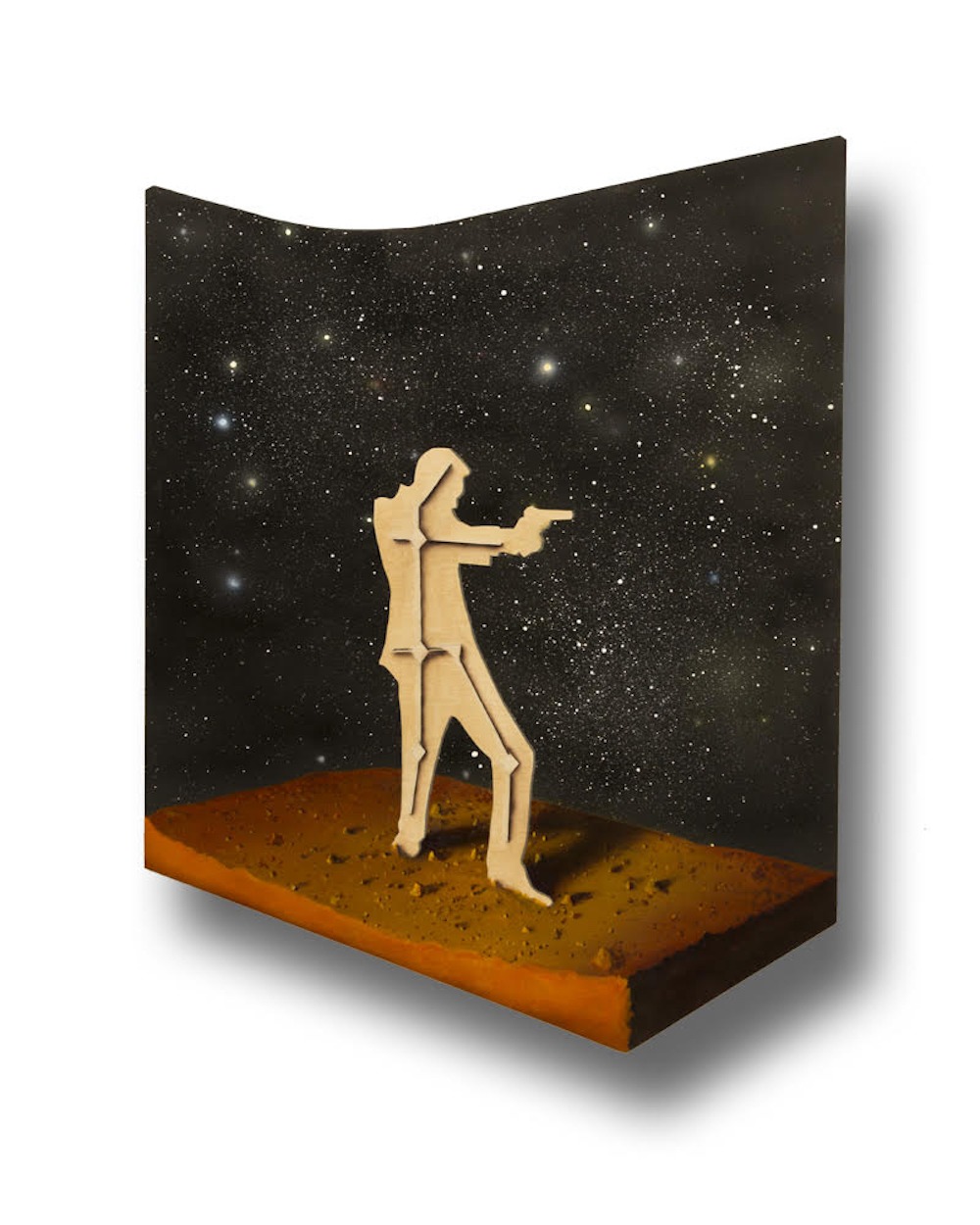

The Soft Takeover of Mars (2019)

Acrylic on wood panel

30″ x 23″

Courtesy of the artist

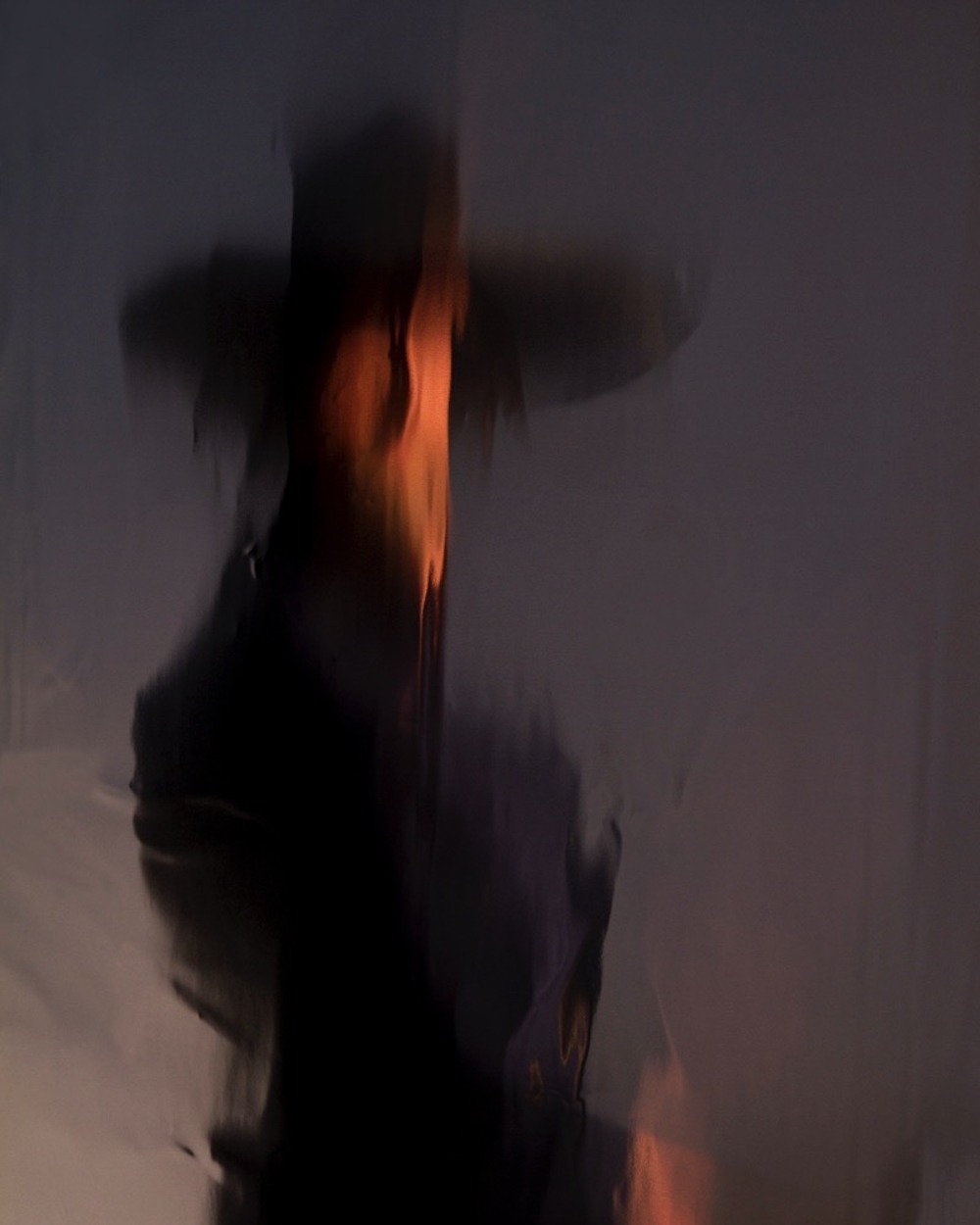

Your new photographic portraits are quite painterly, dramatic even. They’re blurred out using a technique that you don’t reveal. To be they look like swirled up Old Master portraits. Can you talk to me about these?

Yes, the series uses a technique I developed a few years ago that distorts the image in real time making it look more like a painting and less like a photo. There is no digital manipulation and everything you see is what I see in camera. These images contain a painterly quality I was never able to achieve with paints. I love that they are figurative yet ambiguous in their levels of abstraction. Since developing this technique, I have become more aware of Gerhard Richter’s paintings that blur the image; these are another source of inspiration and thought I work through the series.

What is the reason not to tell people about the process?

When you get down to it, the process is irrelevant. What the image is doing to you as a viewer is more of my concern. I think if you disclose certain techniques, people are able, in a way, to write it off and say, “it is what it is.” It’s something I’ve always struggled with in my work: making work that isn’t one note, that is alive and that someone could live with for a long time and it won’t get boring. There is an element of mystery of the actual image that disappears with the process and I just want to give people the chance to appreciate the work. If I take that process way from you, then you can continue to engage, whether that takes the form of trying to figure out the process or just trying to appreciate why I lit an image a certain way. In this sense, I give enough information for how I want it to be viewed and enjoyed.

You’re also working on a series of paintings that incorporates billboards in different way. These can be quite surrealist. These make be think of James Rosenquist, but also René Magritte with their kind of tongue-in-cheek plays with perception. What’s going on here?

Living in LA there are tons of billboards. I started to get obsessed with billboard extensions, which is where the image extends past the traditional rectangle. When seen from the back they perform as ambiguous framed plywood silhouettes against the blue sky. Some you recognize, and some are just abstract forms. They are constantly changing but it has had my attention for a few years now and I am just now finding a way to incorporate this into my work. Growing up in LA and having a family involved in the film business, I was on set a lot and was always fascinated by these sets we see on TV and how we believe it is all real only to see from behind that they are just painted plywood panels. In You Promised Her Flowers for Eternity, we see negative space in the vase and the man and the woman looking at each other. These are flat and just paintings on wood, but cut an angle that forces the perspective. I leave the wood and I paint around it you get to paint different floors essentially. There is something on the other side that we can’t see that the viewer is left to imagine. In that work, it’s the flowers. I’m just giving a scenario. I’ve always liked narrative painting, pieces that tell a story, where there a middle, beginning and end and there are clues for that.

The Locals Called Him Shadow Cat (2019)

Archival pigment print

30″ x 24″

Courtesy of the artist

The imagery you’re working in this series collides a lot of different ideas. It’s Surrealist. It’s Americana. It includes scenes of outer space, the cosmos. Do you think about what your imagery means?

These were the first pieces exploring this idea. I went with it and then I sat back and I wondered, why am I making these? There is something about the space that opens it up and makes it feel bigger. The forced perspective pieces I’ve done in the past have all been contained inside of a box. I opened up the box and let it go off into infinity. Simply put, I’m fascinated with space and I love painting it.

She was taught at a young age to never let the sun compromise her fair skin (2019)

Archival pigment print on handmade rice paper

21″ x 14″

Courtesy of the artist

As a person that didn’t go from a traditional background, how have you developed your community? Because most people do emerge from this more interconnected background.

When I first started painting full time, I joined the LA Art Association, which has been around for a long time and it’s a great place to meet artists. I was still figuring out who I was as an artist and basically doing everything you would do in school I did through them. I still feel a little bit like an outsider artist. I really do because I don’t have that close network of people pursuing art.

Especially because it’s so subjective, anything can be good. In sports, my background, if you’re really fast and you can catch and you can throw you go to the next level. You can paint as realistically as you want. It doesn’t mean anything. Or have the most interesting concepts, but unless the right people are seeing them and the message is getting communicated to right people you just kind of get lost. Nobody told me how difficult it was to make a living or to thrive financially, but you thrive spiritually. I’ve been very lucky and very blessed that I’ve had the last 12 years to have a full-time studio practice.

Who are the artists in art history you most admire?

Magritte, because he made art that really opens the doors of perception. Picasso, because he approached so many different styles. I love the way John Baldessari looks at art, his conceptual ideas and commentary are just plain funny, while being interesting and critical, as well.