A One-On-One With Monica Bonvicini

“I think one strong reason why I wanted to become an artist is that I was terrified by the idea of getting up every day and do the same thing”. With these words, one of the most multifaceted and interesting artists on the Italian scene, Monica Bonvicini (b. Venice, 1965), begins our interview.

Her international career began in the 90s, and her production comes to life through different media and languages investigating issues related mostly to history, politics and society. Thus, to the relationship between gender, architecture and power with the aim of finding, somehow, an ideal of freedom. Her works recount lived events that mark the most intimate part of the individual. For this reason, to understand the work, the user is called to be part of it in some way. Her work makes us reflect on the past to better understand what we are today. Contemporary life is seen through a minimal and direct artistic approach, where the matter and materials that the artist chooses based on the work speak for themselves. In each of them, Bonvicini seeks confrontation with the public, a discussion in which to find new ideas, stimuli and comparisons. Each work is a provocation and is born precisely from an idea and a specific topic that she then develops with a collage, a photograph or a drawing.

Bonvicini studied Art at the Hochschule der Künste Berlin and the California Institute of the Arts (Valencia). Since 2003, she has held a position as Professor for Performative Arts and Sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. In October 2017, she assumed the professorship for sculpture at the Universität der Künste, Berlin. Her sculptures are installed in the Museum of Modern Art in Istanbul, at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in London and in the Harbor of the Oslo Opera House, Norway. Bonvicini has won prestigious international awards including the Oskar-Kokoschka-Preis – the most important art prize awarded in Austria every two years and returned to Italy for the second time after Mario Merz’s victory – and the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 1999. On 12 March 2012, she was awarded the honour of Commander of the Italian Republic. In short, Bonvicini is an artist who researches art at 360 degrees. Bonvicini lives and works in Berlin.

FRONTRUNNER is proud to present a one-on-one with Bonvicini.

Photo credit: Andrea Rossetti

Your production is rather complex and multifaceted, mostly focused on the concept of ‘identity’ as an individual, space, power, sexuality and material. What does the concept of “identity” mean to you, and why did you choose this argument?

To be an artist means to be curious and experiment with ideas and material. As an artist, you do not (only) write books, as an example, but you develop a visual discourse that is using material as language. So, I belong to those kinds of artists who do not do the same things all their lives-long. I do have a series of materials I regularly use, and I would sum them up as mostly coming from the construction world. Architecture is, for me, a huge form of inspiration, probably because of its close relationship to sculpture. In terms of identity, if you think about it, there is no identity without architecture. It is the place where you develop your own identity first: if it is a house, a tent, an institution…your sense of reality is always and firstly connected to what contain you, in a good or bad sense of the word. So, I first choose architecture or the perpetual in movement “construction site” as my main interest, and how we relate to it.

The pandemic made us think a lot about ourselves, or it should have. How did you spend this period from a personal and professional point of view?

I spend the time like everybody else, in a kind of limbo, doing not much at the beginning. I remember that for a while, the large entrance area of my studio was totally empty beside the lonely bike of my studio manager. It was quite a desolate view. Nobody was working, the streets in Berlin were quiet, much less cars, stores closed, no people. Like in the song: “First I was afraid, I was petrified…” Then tired, and then I started working again. Listening to loud music, which I haven’t done in a while, and producing a large amount of drawings which reflected very much what was happening in the world in 2020.

What are you referring to, in particular?

I’m talking about the Black Lives Matter protests, or the fight of the #MeToo movement, as well as the climate crises. I did a video, which is the most abstract one I’ve ever done: a very anxious, psychedelic 8-minute-long projection where nothing real is to be seen, but where the moment of blindness and desire to move ahead is the topic. The title of the work is borrowed from the late British neurologist Oliver Sacks talking about hallucinations. He describes a woman who had experienced seeing a building in changing, flashy colour. She recognizes them as being not a dream, but more like a film, one that she doesn’t really want or choose to see. Like her experience, I See a White Building, Pink and Blue (2020) is a work suggestive of our global, social, and political vision in the current times.

Built For Crime (2006)

Broken safety glass, light bulbs, 5 dimmer packs, Lan Box, airplane cables

Approx. 120 x 1235 cm, height from the floor approx. 150 cm

Installation view: The Sculpture Center, New York, 2007

Courtesy of the artist

© VG-Bildkunst

Photo credit: Jason Mandella

In your work, you play a lot with LEDs, neon as in Not for You (2006), Bent and Winded (2017) and Bent on Going (2019). So, is light a form of freedom that contrasts with the iron chains, ropes, belts, and other recurring materials in your work?

I started working with lights back in 2006 with works like Not for You or Built for Crime, or neon light with Kleine Lichtkanone (2009), Blind Protection (2009), until the very large sculpture, Light Me Black (2009). For the permanent outdoor sculpture RUN (2012) in London, I developed a complex construction for an infinite light within three large letters using more than 8,000 LED lights. Around 2017, for the Istanbul Biennial’s A Good Neighbour, I started kind of weaving LED neon lights together as they would be some sort of fabric, some sort of soft material. I very much like tapestry and the way that they were used on different level to warm up spaces, to tell stories, and at the same time function as high-value art pieces. In that sense, what kind of stories are neon lights telling? Of which spaces do they let you think? All association to neon lights are related to garages, storages, corridors, cellars, prisons or, yes, the museum. They do not really impersonate anything related to domesticity or comfort. They are mass industrial products, cheap and practical. What they make visible is a certain social class and a certain architecture.

Among numerous awards, you received the Golden Lion Award at the Venice Biennale in 1999 along with other artists, all women: a very important moment for the female figure in art. Has anything changed today for women in art?

I’m very glad to see how many good things have changed within the last 20 years. Anyway, I’m convinced that feminism has been the biggest pacific revolution of the last 150 years. So, let’s continue, it is not over yet!

What are you currently working on?

I’m working on very different projects. I will have solo shows in galleries and in institutions, as well as public projects. One large project is related to an architectural installation I first showed in 2019 in Turin, then again in 2020 at the Busan Biennial, Words at an Exhibition: an exhibition in ten chapters and five poems. The work consists of a large wooden structure, a 1:1 replica of a two-family house, and is a reconsideration of what a home is. Following the path of the Buster Keaton movie One Week, this large sculpture will be presented in different ways in each of the different places: the upper floor out of centre, cut in three parts as a [Gordon] Matta Clark, etc.

Where will it be shown?

It will be shown in the utopian architecture of Peter Cook next April, and later at the Bauhaus Museum in Dessau. I’m very excited about this series of traveling shows that will give me and the audience the possibility to always see something else. The sculpture, As Walls Keep Shifting (2020), takes its name from Mark Z. Danielewski’s book House of Leaves and will function as a stage for performances, or concerts, as well as a display platform for other works on mine. Literature has always been something important to me, so quotations and re-interpretations of quotations will also be part of those shows. The studio is also working on an extensive catalogue that will document the different shows, but also many of my works and of others which relate to the idea of home, of losing it, making it, destroying it: from Wallfuckin’ (1995) to In the Kitchen (wet) (2020). Next year, I am also planning a solo show at the Neue Nationalgalerie (Berlin). I have been following and documenting – in parts – the renovation of the building, so part of that process will be in the show. The title of the show, Elegance and Crime, will offer a new take on (or a reveal of a rarely-scrutinized semantic layer of) the Neue Nationalgalerie, its value as a building, as a landmark, and as a cultural institution.

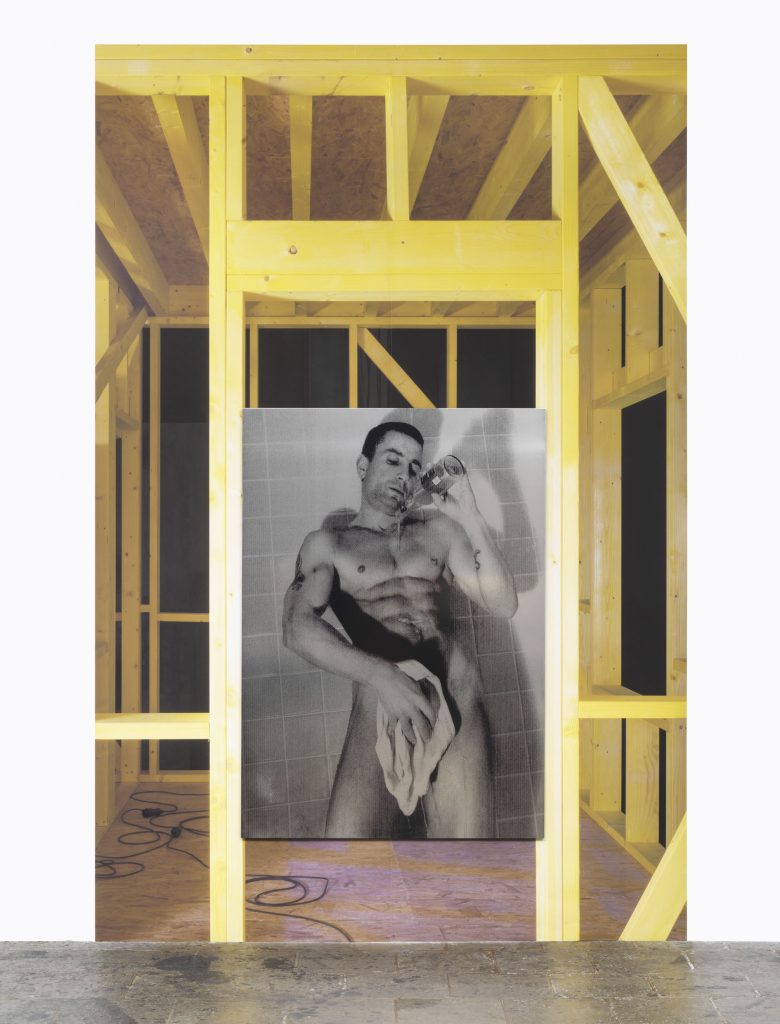

Wallfuckin’ (1995/96)

Black and white video on monitor, sound, amplifier, speakers, drywall panels, aluminium studs, bricks and mortar, white paint, wood panels, door

250 x 310 x 330 cm

Duration: 48 mins

Courtesy of the artist

© VG-Bildkunst

Photo credit: Jan Ralske

What topic would you like to work on in the future?

I would like to work more directly with nature. Those drawings of mine documenting the climate crises from 2007 onward are all about hurricanes and other natural catastrophes. The work, A Violent, Tropical, Cyclonic Piece of Art Having Wind Speeds of or in Excess of 75 mph (1998) reproduced as much air as a hurricane does within the walls of galleries and museum. I love the materiality that architecture can give to totally immaterial material like air. But I would be thrilled to do something outside. I also have an Opera in my drawer: Turandot. Let’s see what will come!

Responses