Digital Empathy: Miltos Manetas

Miltos Manetas is a Greek artist in constant search of technological empathy, feeding on synergies made up of encounters, readings, cultures and places without borders. Having started in Greece to discover new ways to feel alive, his art ranges between hardware and software. Oil paintings, digital canvases, and immersive realities become unprecedented still-lifes situated in floating studios around the world.

“If I go to a place I never stop passing, I always return because my studio is everywhere, even if a friend can become an enemy. It becomes impossible for you to ignore me, because somehow I force you to work with me and my presence becomes an avatar wherever I build my floating studio page. This way of being is very Greek.”

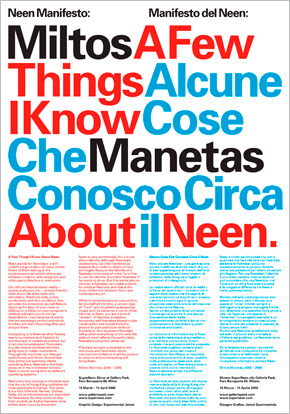

After reading Neal Stephenson’s post-cyberpunk novel Snow Crash, Manetas’ work Metaverse was created in New York in 1998 in collaboration with artist and architect Andreas Angelidakis. In 2000 he founded NEEN, an artistic movement offering the public a new way of understanding and experiencing art. It aimed to conflate the new technology of the time with art and poetry, launching from the Gagosian Gallery in New York. “I think this American experience started NEEN,” he says, “with a sort of virtual simulacrum dedicated to art and architecture. In addition to mine, there were studios friends including Takashi Murakami and Vanessa Beecroft.” How was NEEN conceived? In 1995, for the exhibition Traffic, art critic Nicolas Bourriaud (who helped launch the Relational Aesthetics movement in the late 90s) brought together artists Maurizio Cattelan, Vanessa Beecroft, Gabriel Orozco, Jason Rhoades, Rirkrit Tiravanija, and Manetas, among others.

Manetas was born in Athens in 1964. He studied at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera in Milan. Named by The Guardian as “El Greco of the geeks”, Manetas’ work has been shown at international venues including the Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris), the 2018 Athens Biennial, the ICA and the Hayward Gallery, both in London. For Manetas, who divides his time between Rome, Athens and Bogotá, every journey is synonymous with interior research. In recent years, specifically in the Colombian capital, he found inspiration for the next NFT and Floating Studios projects that he’s carrying around Europe.

FRONTRUNNER is pleased to present a conversation about the future, from an artist who witnessed it from afar.

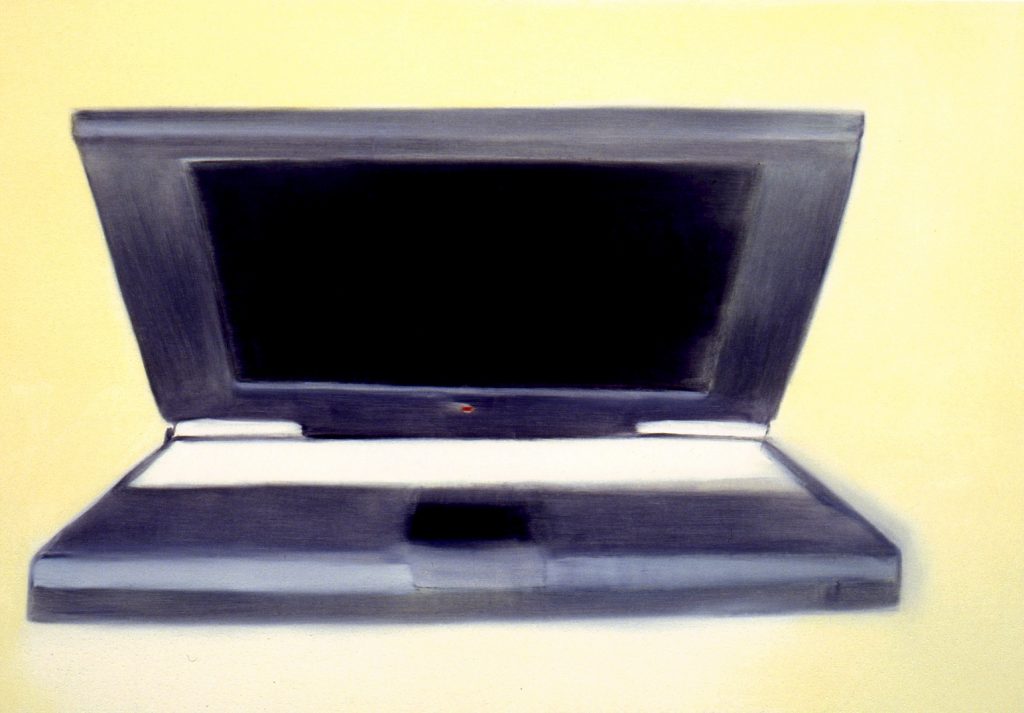

In 1996, the French theorist and curator Nicolas Bourriaud invited me to participate in his exhibition “Traffic” at Bordeaux’s CAPC. With this show – which resulted in becoming the most important exhibition of my generation, Bourriaud was introducing the idea of Relational Aesthetics: “a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space.” Most of my friends were included in that show, between them Maurizio Cattelan, Vanessa Beecroft, Gabriel Orozco, Jason Rhoades, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Pierre Huyghe, Philippe Parreno, Liam Gillick, Douglas Gordon, Carsten Holler, Xavier Veihlan and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster. Relations- Bourriaud had noticed- were at the centre of our Modus Operandi, with a certain type of aesthetics rising as a result chosen by the attitude of each artist. Our attitude and our tools: at that moment, I was supposed to be “the one of the computer”. I had bought a laptop and without really knowing how to use it yet, I was bringing it everywhere. We were doing performances together. “We”, myself and my laptop, we’re connecting with…the wall. When Nicolas revealed his concept of Relational Aesthetics, it felt a bit antiquated to me, mostly because of the way it sounded. I remember asking him, “Would computers like it?” Back then, we didn’t use the Internet that much. Still, computers had already become important for our lives.

My laptop was called PowerBook and it was important for me the way a “friend” is important. There was another friend; I had also acquired Apple’s first digital camera, QuickTake. Such names, PowerBook, QuickTake etc. were important because they would make it clear for us that the hardware they were representing was not the usual machines we were accustomed to. That the presence of digital machines was a peculiar presence”.

These objects traced a new historical period in the world of art, as well as technology. How did the neologism NEEN come about?

Observing these new machines which had start registering their life and ours, machines that looked as if they are thinking, I realized that there’s something new to be said, a new narrative. It was as if these machines were inhabited by some kind of not-human artists. We had started working together with that “people” now so it was necessary that someone would come up with a proper word that would represent all that.

Inspired by DADA – which mistakenly I considered a palindrome – I was looking for a term. Because nobody would invent it, I continued calling it what I was doing: “Relational Aesthetics ‘. Then, one day, on a flight from New York to Europe, I read in Wired Magazine about LEXICON, a California- based company responsible for the terms PowerBook, Pentium (Intel’s fifth-generation microprocessor), BlackBerry and many others. LEXICON, whose own name means “Dictionary” in Greek, was asking $100,000 to coin a term back in 2000. I found that money and about five months later, I received a fax with a list of candidates. Between those, there was NEEN, an uncomfortable-sounding little word (which was a palindrome) and which neither my pals on this project nor the people from LEXICON liked back then. It wasn’t coined by humans, but by a proprietary software the company was using. The linguists had simply input the word “screen” and the software squeaked out “NEEN”. Instead, everyone seemed to like “Telic”, a word coming from the Greek “Telos” (which means “end”): we have reached the end of something, and now there will be a change. Then, my very young Japanese collaborator said, “I wanna be a NEENSTER”, which we misunderstood as “NEENSTAR.” I decided to go with NEEN, which in English has the same sound as an old-Greek word which comes from the Latin “Nunc”, meaning, “exactly now, not a second later.”

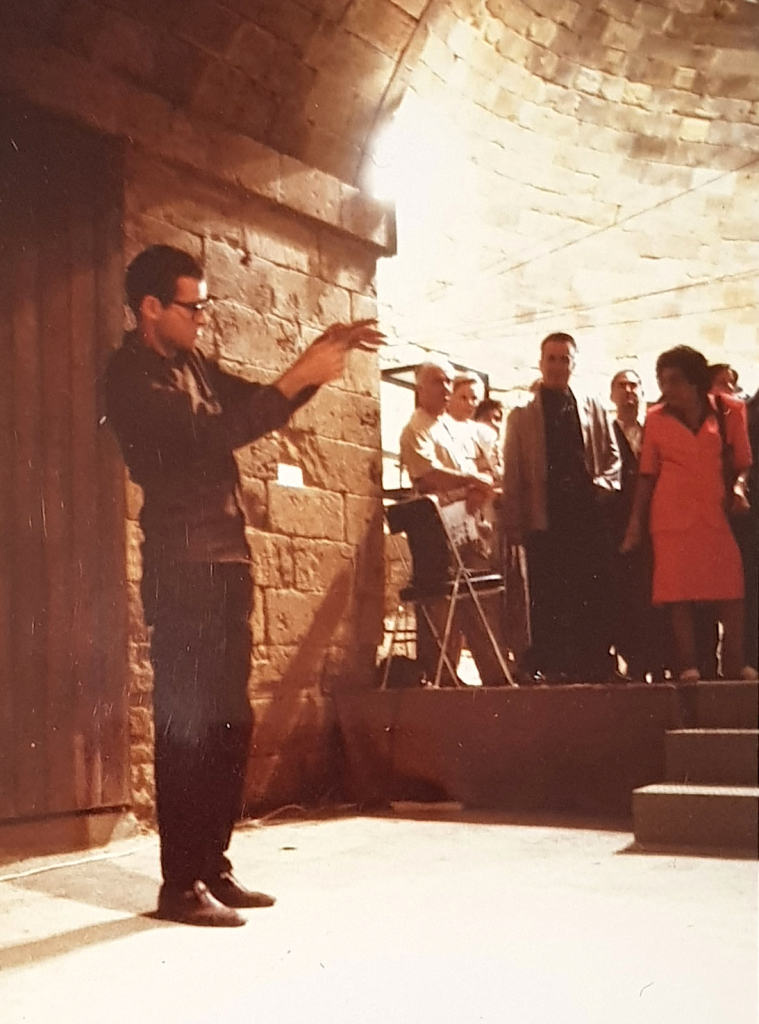

NEEN was officially born with a conference/performance at Larry Gagosian’s gallery in Chelsea, on the last day of May 2000. That was at the same time the stock of the Silicon Valley companies collapsed: The World and its computers were embarking on a period of “new realism.” Days of Telic, NEEN was desperately needed. Mai Ueda and I left New York for Los Angeles and we opened the ElectronicOrphanage: a space where we would invite creative young people and I was paying them 8.00 USD per hour to do nothing. They could play video games, or get lost as much as they wanted on the Internet-Safari, but if they would start making art or design, they would lose their job. That’s how the first NEEN works appeared, little flash animations that lived on the web. A few months later, the first early NFT also arrived.

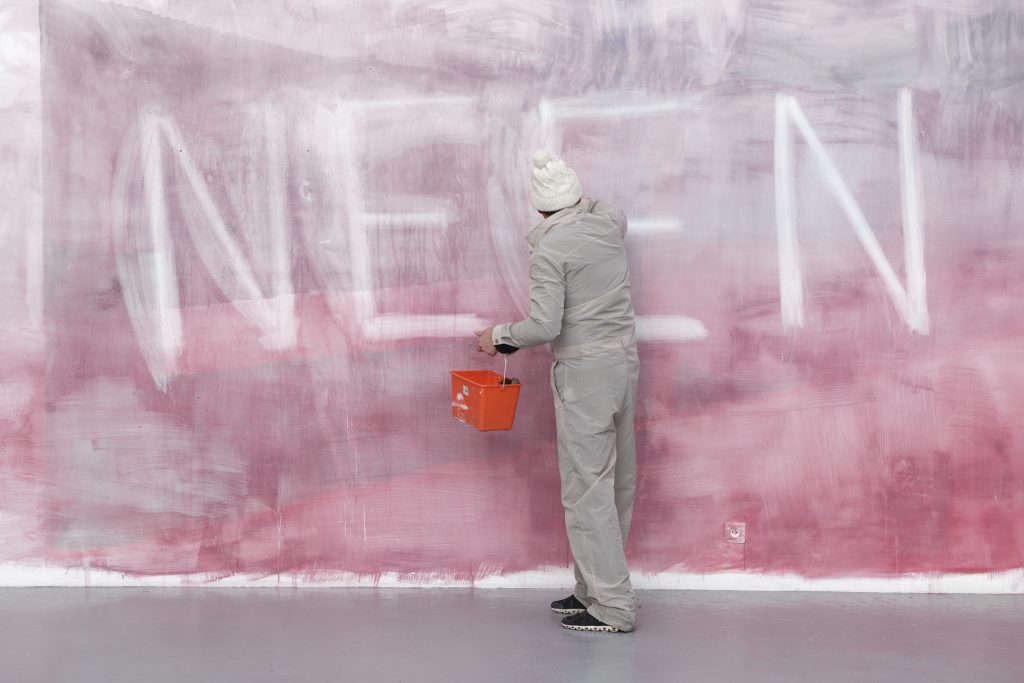

Manetas Floating Studio, The World We Live In, Paris (2021-22)

Installation view

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Hussenot, photo by Aurelien Mole

What was the first work of the movement?

ElectronicOrphanage was a storefront in Los Angeles’ Chinatown. Its walls were all painted black, apart from one we painted white where we were projecting whatever was happening on the desktop of our computers. You could watch these projections from the large glass windows of the space giving way to a pedestrian road filled with art galleries. There was a huge contrast between them and us: our space was always empty and looked like a webpage that had materialized in the city. That situation gave us the idea to start using the Internet in an analog way, too. Internet that escapes the screen and meets with reality in a cyberpunk way. We started creating back then, what many years later in the context of the first Internet Pavilion for the Venice Biennale, would be called “Internets”.

There wasn’t any drinking water at the ElectronicOrphanage, so we used to drink a lot of Evian. Mike Calvert erased the Evian logo from the bottle’s label and left only the famous mountain against a pink sky. He made from that image a desktop pattern and this is how the first NEEN work was created. Only recently, I found out, he had borrowed that Evian Desktop Pattern from a Japanese guy who – as far as we know – is not an artist. That’s very important because it confirms our theories for NEEN: it’s not important that the work is made by a specific person as far as it relates to that person’s post-media persona. The work, in this case the very first NEEN artwork, is attracted by your identity because you are becoming the Operating System.

So with “NEEN-Star“, a new figure was defined.

In NEEN, the collaboration with computers and networks is very important. We start creating single-serving websites, intended as artworks, from as early as 2001. Adding “.com”, “.org” or “.net” on a word or a phrase makes the work a unique one because there’s a contract with the domain registration guaranteeing that. The first work of that kind was my www.Jesusswimming.com, where Jesus is swimming instead of walking on the water. It was one of the first NFTs ever, as it’s for sale as a “Non-Fungible Token”. After this work, everyone in NEEN started making websites to exhibit as artworks and to sell. Rafael Rozendaal, who back then was a bit older than 18, had a contract made to give an extra guarantee, but it wasn’t really necessary as there was already a contract with the domain provider.

Your JacksonPollock.org project was one where anyone could paint on a digital canvas: Pollock being the exemplar of Action Painting.

This was a diamond! A miracle-work that not only I didn’t create formally but also I didn’t think of doing! A NEEN work that became mine only because I was obsessed with Jackson Pollock (I decided to become an artist after seeing Pollock’s monograph). The piece began when Rozendaal found online some code – an experiment by a programmer – that was producing an orange drip. In typical NEEN-fashion, he sent it to me so I could appropriate it. I managed to make this code producing multi-coloured dripping. At that point, Mai Ueda suggested that I should put it online. I always thought of Pollock as a programmer-artist. Pollock had borrowed dripping from Janet Sobel, an amateur artist who had a show at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery, where Pollock also showed. Pollock changed the scale of Sobel’s canvases. He updated her protocol, and I did the same by turning the dripping digital and putting it online. Drip paintings now are not just large, but ideally infinite, and I inherited Pollock’s legacy.

Why are you dedicating a portion of your production to Julian Assange?

I am a painter, and my work is the work of a portraitist. I paint the world that surrounds us: cables, hardware, people looking at their computer screens, playing video games. But I also paint the leftovers of artificial intelligence: the pictures and design and videos we see online. I’d been painting the Internet for many years, already. I started back in 2002, and in 2018, I did a solo show at Rome’s MAXXI called Internet Paintings. Julian Assange is the Marilyn Monroe of our day: like Monroe, the image of Assange captures the public imagination in a very significant way. Painting Assange’s portrait was imperative for me and I choose to do so by making a portrait for every day Assange spends in prison. There are also personal reasons behind that choice. For ten years, I have embarked on a quest for some kind of personal Marxism, a Marxism that isn’t necessarily communist or socialist but for sure is a renegotiation with Privilege. Assange becomes some sort of an avatar. Although Assange himself probably wouldn’t accept that he – and myself – are Marxists the way Jacques Derrida suggests in his book Specters of Marx.

EVIAN DESKTOP PATTERN.JPG (2001)

Unique

Courtesy of the artist and Miltos Manetas

So is Assange a meme?

Julian Assange is a person, and a meme too. I’m into working with memes because after all, everything we do in art eventually becomes a meme. The origin of the term meme is in biology, not on the internet. It was introduced by Professor Richard Dawkins and it means “a unit of cultural transmission”. How do we turn a meme towards some direction, a Marxist direction? For me, Marxist direction is turning something to some kind of power, turning it so that it enforces – socially – anyone who relates with it. This is not power over others, but power over one’s self. The response to Lenin’s “What is to be done?” to demonstrate that we are not powerless, after all. That’s why this work is called AssangePower. I’m giving them to whoever asks for them first on Instagram. In this way, whoever receives it “pays” in involvement. It’s the opposite of using the power of money the way collectors usually do to own something. With AssangePower, there’s a transfer of generosity starting from Assange, then myself, then the collector, etc. I’ve painted 350 portraits already. The duration of this work depends on how long Assange is in prison I’ll go on painting him. The British Ministry of Justice is my collaborator on this project. In 2020, I presented The Assange Condition at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome. There were forty works included in that show but because Assange is still in prison, I kept the doors of the space closed to visitors and the show could be seen only through a social media interface.

Is the “Floating Studio” a travelling project?

For me, It all started with Neuromancer, a book a friend gave me to read in 1992. I had no idea about computers or Cyberspace then, and as I learned later, neither did William Gibson when he wrote the book in 1984. We both start fantasizing about computers and networks, Eventually, everyone was influenced by that book, or at least the entire tribe of programmers from Silicon Valley! Neuromancer is the script of what became Cyberspace for real, but also of the Metaverse: a name that appeared only ten years later. There you can find characters similar to myself and even to Assange, people that looked futuristic when the book was written, but that are now ordinary. There was something very familiar on Gibson’s Cyberspace that inspired me, and I decided to make a show Collegamenti (Links) (1992) dedicated to it. I envisioned a large wall of Via Farini in Milan was now the interface of the Internet. To produce the sensation of connection, I inserted a few cable sockets with jacks plugged in, only instead of cable, I used an elastic cord. The instruction for visitors was that they should connect with the wall “trying to feel a bit demented”. I also drew connected stick figures on the wall.

Many years later, when John Perry Barlow (legendary lyricist for The Grateful Dead) became my friend, I started understanding Collegamenti. Barlow not only was Gibson’s closest pal when Neuromancer was written, but also was the one who had suggested the term Cyberspace. Both Gibson and Barlow were heavy users of Ketamine. Cyberspace was designed on memories of disconnection and if I was finding it so attractive, it was because I used Ketamine. Barlow, to make his point, brought me to his apartment in New York and administered to both of us a couple of intramuscular doses. I remembered the space-time warps Special-K produced, but I had never injected it into me. The environment around us suddenly became as empty as a URL that has trouble loading. Thoughts and objects were still there, but their presence was ghostly, like the shadow of a Folder on a computer desktop. One could just “highlight” reality while waiting for it to boot up. About ten minutes later it did, and I found myself shaken back and forth like a doll in Barlow’s arms. A short video sequence taken that night was turned later to a Collegamenti artwork.

You’ve already presented this in Paris and Rome, and it will soon be in L’Aquila and Naples.

Courtesy of the artist

Floating Studio is my “Searching for Time Lost”. I am building environments where I can revisit the past, what I did, and what has happened to me. Naples’ Floating Studio is based on 1992’s Collegamenti and we are working to make it a totally immersive environment. Mixing soap and paint-pigments, I have invented a “Computing Paint”: a very rich, fast and fragile tint that I apply on the walls of galleries and Museums. That way, I am appropriating those walls. They become my diffused studio, some temporary, others permanent. I started in Paris at Galery Houssenot by projecting images from the Virtual Worlds that myself and Andreas Angelidakis built in the early days of the Metaverse in the 90’s. Now at MAXXI, L’Aquila, and Andrea Nuovo Home Gallery in Naples. That last one is curated by Massimo Sgroi, the only curator in Italy who, as far as I know, has read Neuromancer when it was published and considered its consequences. Once painted, the wall paintings of Floating Studio are turned into Teleports. They are first photographed and filmed, then they are minted as NFTs. Those NFTs, which I call “NFTrelacional” because they relate to real and digital space, are the foundation for the Metaverse of my new Digital Floating Studio.

Why did you move from London/New York/Milan to Bogotà, Colombia?

Ten years ago, I left for Colombia to study Marxism which means for me discontent with Capitalism from a point of view of privilege. I was in Colombia when the NFT exploded, bringing with it the possibility of a huge reform to the negotiation of Special Privilege: the more exclusive of privileges are those related with what we call “reality”. I consider the NFT a second Russian Revolution: if it will not be stopped, it will change post-capitalism deeply. There will be a world before and after NFTs, as there is one before and after the Russian Revolution for Capitalism. Especially privileged citizens such as myself should recognize our special privileges, sometimes even celebrate them or accept their consequences. In February 2021, my phone start suddenly ringing again in Bogotá, where usually nobody calls me. Gagosian, The New York Times, the Times in London wanted to find out about NFTs. But as I was out of the loop for years, I had no idea. As I was speaking with them, I start reading online about Blockchain and I started feeling responsible!

In your opinion, is it necessary to be restless, or rebellious to be an artist?

Absolutely not. There’s no need to an artist to be rebellious, especially a visual artist which is something anyone can be because everyone can (theoretically, at least) see and represent the world. But to be a citizen, to participate as a citizen and not as a slave in the Society of Privilege, to be a rebel is imperative. Someone like Julian Assange, a technician of post-capitalism, can’t but be a rebel, an extremist of shorts.

Particularly during the pandemic, social networks and the Internet have been important elements in our lives. Do you think we are living, even unconsciously, at the end of our feelings?

What we are now living is the sequel of post-capitalism in its encounter with Artificial Intelligence. Marx had already noticed, and in “Grundrisse”, he writes about “General intellect”, meaning the transformation of general social knowledge to a direct force of production. In this situation, machines become organs of human intelligence. To keep our humanity, we need to keep ourselves in a constant re-negotiation with the offers of the Free Market, especially its many gifts of “free meals” when it comes to tools of communication. My personal response to social media is to use them to…read books! Whenever I try reading Derrida, theory or philosophy, I’m falling asleep. But If I’m doing it on Facebook and Instagram, I can go on for hours and understand deeply the content of what I’m reading. Maybe I can even find some way to use my online reading as a weapon. Social media is our opportunity to become many, to be all of us, to feel the world together. It’s empathy, but it has to be re-invented by each of us every time we are using it. We can reach Togetherness, what you feel I feel, but we should prohibit them to make us feel whatever is prepared for all of us.

What is the most interesting media out there, also among social platforms like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram?

I often receive this question and I have only one answer: Woman is Her New Media. I hope that my answer will not cancel this interview.

Responses