Photographing Limbo: A Conversation with Ronit Porat

Born in 1975 in the K’far Giadi Kibbutz in Northern Israel, Ronit Porat is a multidisciplinary artist who lives and works in Tel Aviv. She studied photography and digital media at the Hadassah College in Jerusalem as well as Fine Art at the Chelsea School of Art and Design in London and completed her MA. Porat’s collage-like procedure may be classed as a Dadaist photomontage method. She uses these images, which she alters by means of trimming, as well as private photographs, in order to allow new narratives to arise and historical boundaries to become visible in her installations. Her solo exhibition, Paradiesvogel (meaning ‘Paradise Bird’) was mounted as part of a city-wide Artist-Meets-Archive series in Cologne, presented at the Kölnisches Stadtmuseum.

FRONTRUNNER speaks to Porat about this unique opportunity to image-hunt, the pressures of global politics on image-making, and how women photographers continue to hit roadblocks in the year 2019.

First off: would you classify yourself as a photographer or as a multidisciplinary artist?

In the last three or four years I’m more of a multidisciplinary artist. I haven’t held a camera for the last nine years. I’m coming from photography but an artist who uses photography – that’s my main passion – but I deal with images.

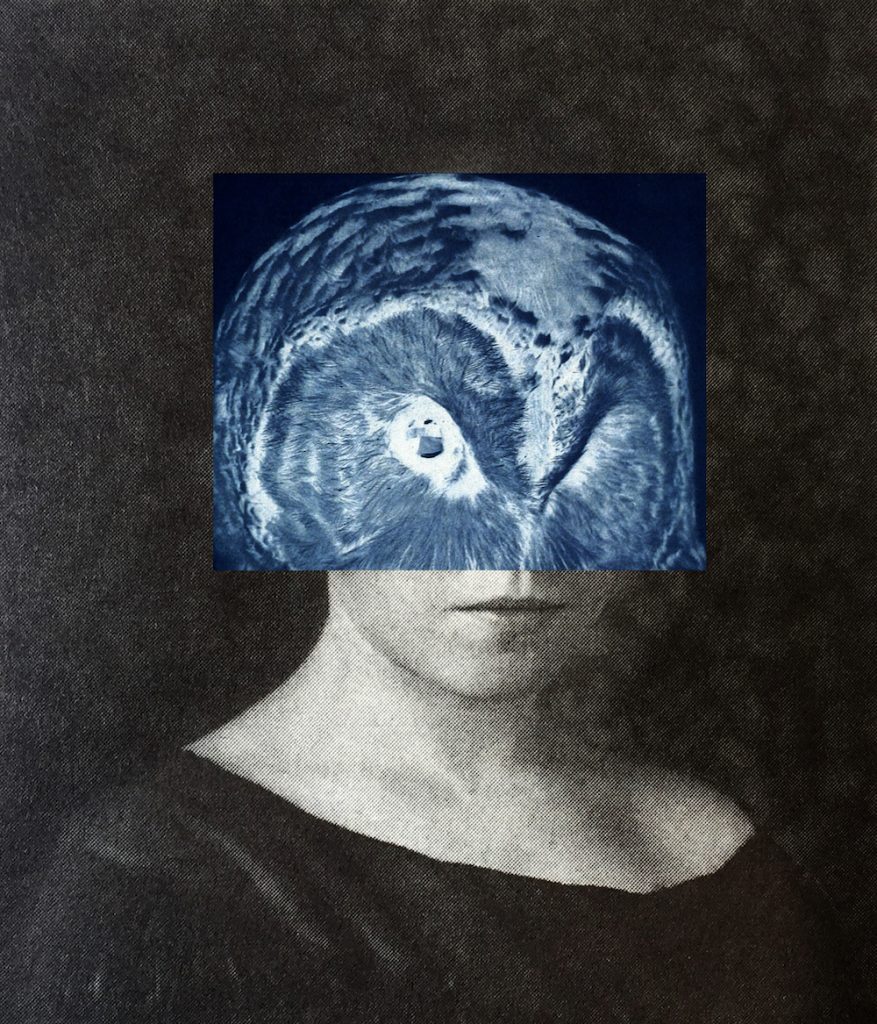

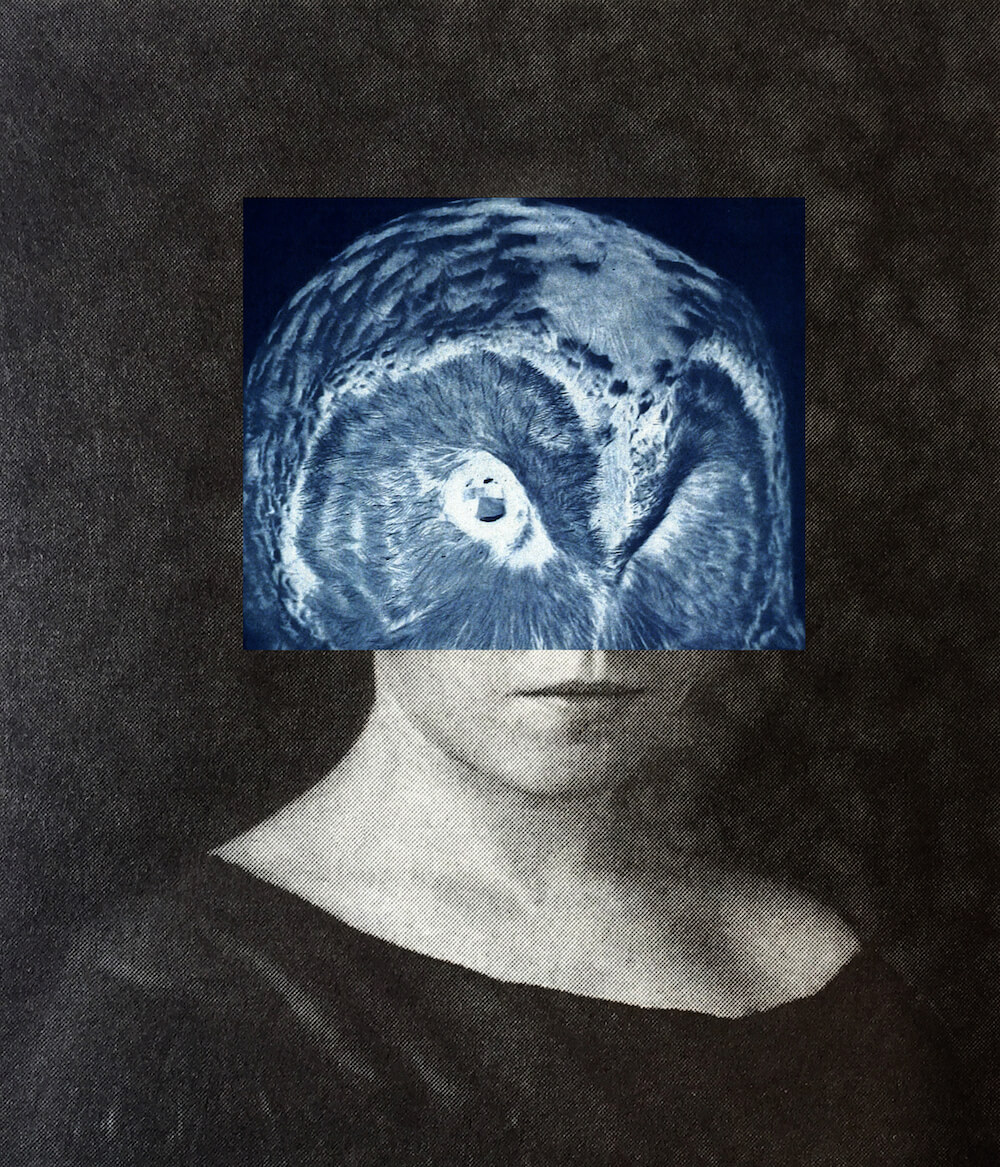

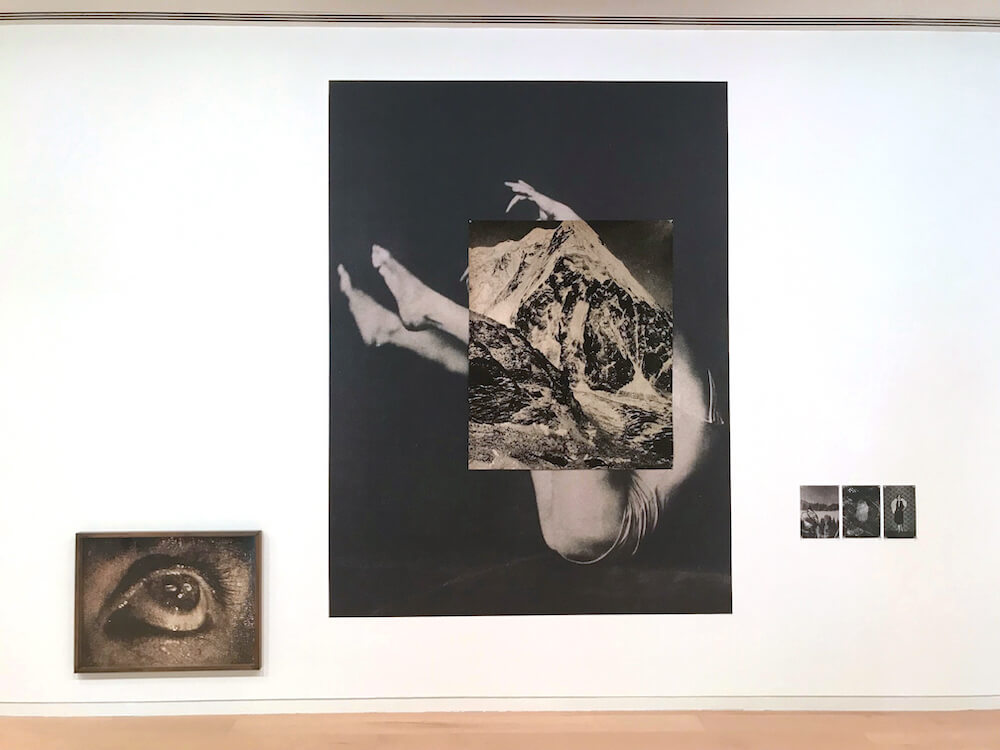

Untitled (2019)

From the graphic collection of the Cologne City Museum

Photo collage

Image courtesy of the artist and Kölnisches Stadtmuseum, Cologne

Your most recent solo exhibition at the Kölnisches Stadtmuseum was, then, perfectly appropriate as part of a city-wide series where the artist-meets-archive. When you first came to Cologne, were you overwhelmed? Excited? A little nervous?

I was nervous, I think, and excited. First of all, I was invited by Photoszene (Festival) – this artist-meets-archive – and they said that my archive would be city archive. It was important for me not to be the Israeli-Jewish to come to a German archive, any German archive. My interest has been, for the last nine years, the Weimar Republic which was in between the wars. Cologne has a very interesting history because after the First World War, the British were there until 1926 and when they left in 1933 it was crazy times! Approaching an archive is always a question: what do they want to expose or what do they want to hide from me? In the same subject, even though I’m focused on this time between 1918 and 1933, I didn’t want to know what happened in wartime and I didn’t want to know if they had any Nazi imagery or objects.

So you worked with pre-made images.

Exactly. When they did an introduction for me, when they gave me a tour, they said, “Oh, we have 20,000 postcards here.” I said, “Hmm…postcards!” It’s a way to communicate with people, it’s a way to send some contact abroad. The truth is, when you enter the archive there are so many things so something needs to catch your eyes. This is why I started focusing on the postcards.

Let’s talk about Charlie Evens. I was fascinated by the idea of this British soldier, who seemed to be very much not-at-home in [post-World War I] Cologne, someone who seemed to be without his bearings. Did you begin to have any empathy for him or was he just a hapless soldier stuck in this kind of limbo?

I think both, in a way. I found fifty postcards from him. But this is really important for me: I cannot read German or speak German. So suddenly I could read! This soldier doesn’t write much to his wife. “This is another view of the bridge”, or “This is another cathedral” –

It’s very mechanical.

Yeah, there’s no emotions. They were field posts, though. You don’t send field postcards with a stamp. I’m just much of it was censored. I did have emotions for him, because I’m sure he missed his wife and his children in London and he’s isolated. Being a soldier is not a good thing; you’re not supposed to have empathy for a soldier on the German side. For me, being neutral between British and German, and being in the (Israeli) Army and coming from this kind of mentality which I don’t like, I could easily feel that he’s lonely and doesn’t know where he is. It’s this limbo, it’s exactly what you said. I think it was a limbo.

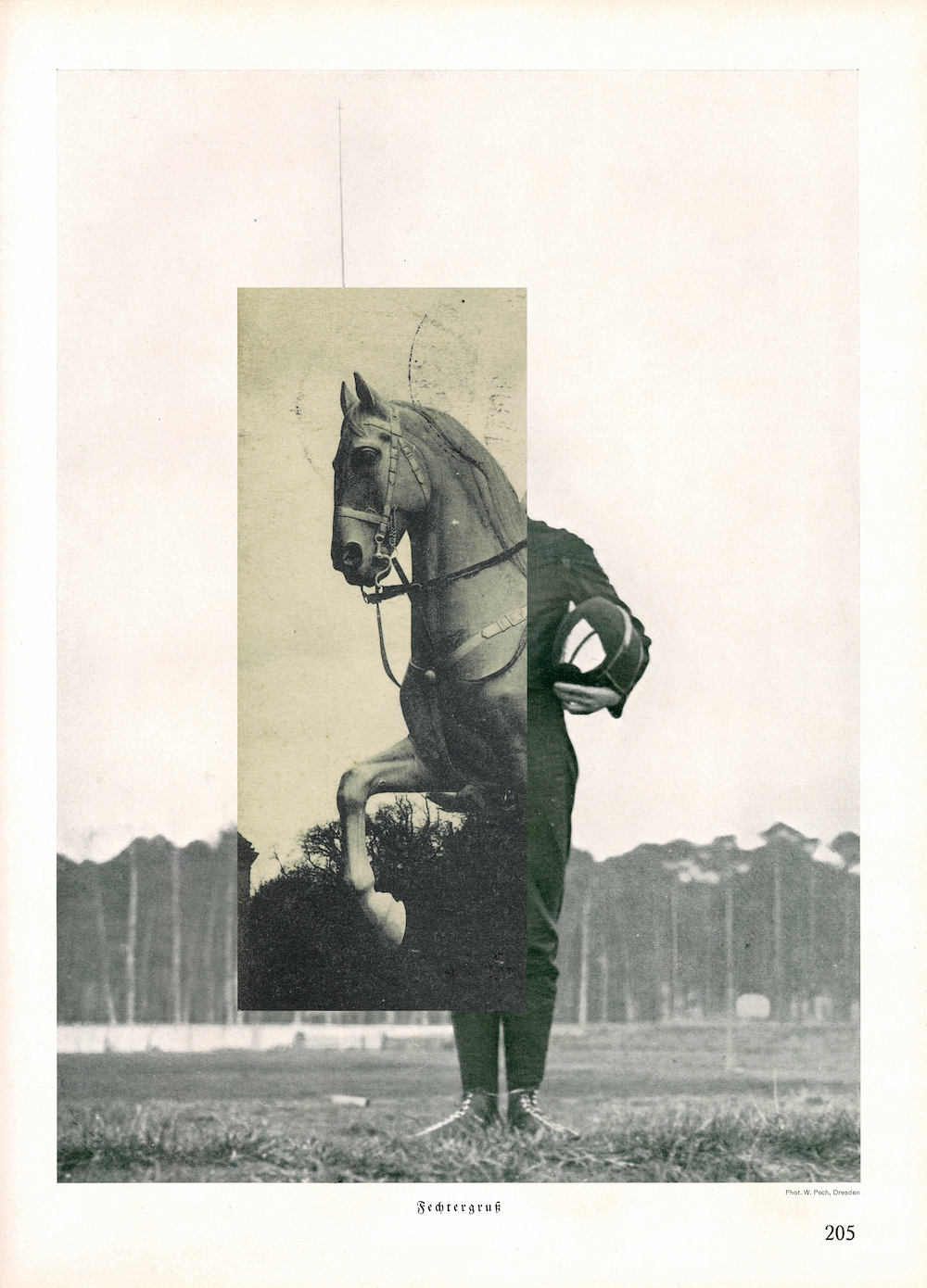

Beyond Charlie Evens (he was just one thread of these dynamic images that you put together), the most arresting images were those with animals. Were you drawn to animals within the archive, or is that something that naturally developed in the process?

I was drawn to animals. It’s difficult because when you go through 20,000 postcards, you need to find some anchor. So one was Charlie, the second is animals; I do use them to transfer some context. When I found a flamingo, I was so happy or the leopard. And then, it’s about collages: it has to do with Dada and Surrealism. Whenever I would do exhibitions in archives, I would look for animals.

Leopard (2019)

From the graphic collection of the Cologne City Museum

Photo collage

Image courtesy of the artist and Kölnisches Stadtmuseum, Cologne

The image in your exhibition that I’m consistently drawn to is the half-image of the woman and the owl: the one subtitled, “The neighbours claimed not to have seen anything unusual.” The way the image is sort of keeping watch, of being vigilant – I think it’s a kind of metaphor for the way you are right now.

I didn’t think about it, but it’s true. Some people who know me think it’s a self-portrait. I cannot be sure about anything, especially about how technology is running so fast. The way we use images, now, it’s everywhere. I do believe you have to ask questions, you have to ask where you are.

It’s very important for me to stay simple. But as the caption says, it comes from like where I come from the kibbutz where everyone [around you] is in your life.

Untitled, 2019 (Luise Straus Ernst)

Photo collage

Image courtesy of the artist and Kölnisches Stadtmuseum, Cologne

Animals have the incredible ability to be anonymous, and that they meld so seamlessly with these thousands and thousands of people that exist in the archive. They each take on the other’s dynamism, and they would have never crossed paths in the real world.

It’s using history and photography. I didn’t take any pictures, I just grab and appropriate these images in order to talk about today and talk about my own biography. Working in Cologne, I know I said I didn’t want to be the Israeli artist in Germany, but my grandmother is from Dusseldorf. So, there are all these layers that I use.

You spoke about your identity. In terms of national identity and politics, we often encourage our artists and people we interview to be open with their opinions and leanings-

What I meant was that my identity should not be taken for granted in that I would [just] talk about the Holocaust. I have very, very clear opinions about politics. I am extremely worried about what’s going on in Israel, all around the world, and how it all shifts to the right.

Very briefly, as an artist, how would you communicate what’s going on around you right now in Israel?

First of all, it’s a government in transition. A recent film about a lawyer, an amazing lawyer, was asked not to be given the National Lottery (Mifal HaPayis) money. I think that it means in these times, being an artist means being an activist. For me, it’s clear that when I choose to be an artist, it’s a political step. To talk about the occupation, I’m not interested in talking about it directly. Artists from the left-wing are being followed, some people cannot cross through the airport without being questioned.

The Sentence (2019)

Installation view

(Friedrich Seidenstücker, Untitled, Scherl’s Magazine, May 1930, G. O. Dyhenfurth, Untitled, Scherl’s Magazine, November 1930)

Image courtesy of the artist

So there’s pressure. You’re sensing that maybe not you, yourself, but the environment for artists in Israel is becoming more pressurized.

Yeah. This feeling that you have that someone is following you – let’s not talk about money – there is a question whether you should take money from the government, or not. As an artist, by taking the money, I can make any kind of work that I believe in and no one would stop me. In Germany, I was surprised; how they’re not so political. In Israel, you have to stay awake. All the time.

Do you think the way in which you use images could be used to subterfuge the current system of how women artists (and photographers) are treated in the art world or the world, at large?

It’s a difficult question. But when you look at photography, and I do want to talk about photography, it’s a male-dominant world. In Israel, there’s this photography prize (the Lauren and Mitchell Presser Photography Award), it’s been given for five years, now. I’m the only woman whose won it. I want to believe in what you said. I don’t give up. How come I’m the only woman photographer who has won this prize? It doesn’t make sense to me in 2019.

What do you think is the next movement forward in your practice?

I feel I’m at a junction, actually. I’m not sure because I would like to see more and work on more archives, because it does feel like a political act, by the way. To expose what they’re hiding and why the archives are opening right now to artists. But, I feel that the practice of archiving is going to change soon. There’s a lot of unknown[s].

This interview with Ronit Porat will appear in FRONTRUNNER’s Spring edition, coming out in May 2020.